She was born around 1595; that she encountered Captain John Smith immediately after the arrival of the first English settlers at what was to become Jamestown (named after King James I of England) in 1607 (in the most prominent version of the story of this encounter she rescued Smith from death at the hands of her father, Powhatan, chief of a powerful Native confederacy); that she helped the people of Jamestown and continued to have a relationship with Smith; that Smith was injured in an accident and returned to England in 1609, Pocahontas believing him to have died; that she was abducted by Captain Argall in 1612 and held captive in Jamestown by the English; that she was converted to the Christian faith in 1613 while living in Jamestown; that she married John Rolfe in 1614 and that she gave birth to her son Thomas in 1615; that she traveled to England in 1616 and was a great success as the 'Indian princess' now called 'Lady Rebecca' at the English court; that in January 1617 she attended the famous Twelfth Night masque; that she was visited by John Smith during her stay and that they had one last conversation; that she died and was buried at Gravesend in 1617 on her way back to America.

In the various retellings of her life, Pocahontas's narrative often falls into two parts: her friendship with John Smith, the 'rescue' incident, and Smith's return to England constitute the first part; the second part includes her captivity among the English, her conversion, her marriage to John Rolfe, the birth of her son, and her visit to England.

In all these variations on the level of discourse, the underlying story of first contact takes on mythic significance as an allegorical narrative of the birth of a new (American) society. It is also the first American love story between the colonizer and the colonized which has us believe that Pocahontas was "sacrificing her life to rescue her (White) love object from her barbarian tribe, a reading which excludes the narrative of rape, cultural destruction and genocide.

To understand the troping of Pocahontas as a paradigmatic 'new world' woman and a female 'noble savage' we need to first contextualize her in a discourse that at the time of the first English settlements depicted the Americas as an allegorically feminized space. In North America, the practice of imagining the continent or its regions as female is also evident in Walter Raleigh's naming of 'Virginia' at the end of the 16th. The gender-specific attribution of America as 'Virginia' presupposes a male traveler who encounters the (virginal, i.e. empty) feminized space and takes possession of it; it is thus highly suggestive of a sexualized relationship between both, which is constructed as a libidinal bond between traveler and territory

The ambivalence that such gendered representations may entail is paradigmatically encoded already in a late 15th-century engraving of "America" by the Dutch artist Jan van der Straat on a 1619-copperplate by Theodor Galle. Amerigo Vespucci 'Discovers' America

Task and questions : composition of the painting. Oppositions. Nudity. Attraction vs repulsion. What is shown/hidden.

It depicts Amerigo Vespucci's encounter with an allegorical female figure that represents the continent named after him. Vespucci is equipped with all the insignia of a European explorer (flag, cross, and astrolabe), while a voluptuous America lies naked on a hammock, stretching out her hand and beckoning the visitor to come closer. She is part of a pastoral scene, tempting, seductive, and enticing. A closer look, however, reveals disturbing details: in the background of the picture, Natives are roasting something over a fireplace that looks suspiciously like a human leg, and another leg can be seen next to the fireplace. Eroticism and cannibalism here appear side by side, and the dangers of intercultural contact are envisioned; for all the claimed superiority of the European traveler in terms of religion and technology, the alterity of the Native is perceived as tempting and threatening at the same time and thus seems to be beyond the Europeans' control.

At the same time, this scene of seduction conceals European colonial aggression toward the indigenous 'new world' population behind a myth of erotic encounter, perhaps even love, correlating the relationship between Europeans and Natives with the allegedly 'natural' order of the sexes: the distinguished European male is to the 'new world' native as man is to woman: i.e., superior

The allegory of America as the 'Indian princess' thus paves the way for the troping of Pocahontas in first-contact scenarios against a backdrop of the foundational mythology of the 'new world.'

The label "Indian princess" refers to her status as the daughter of chief Powhatan and describes Native tribal relations using the European classificatory system of aristocratic distinction which obviously is itself an act of symbolic domination. Therefore, the first English narrative about the first permanent English settlement in the 'new world' centers on the story of a woman native to the American continent who is discursively appropriated and put to use in various guises for the purpose of legitimizing European conquest: as an allegorical representative of the 'new world' in accordance with the connotations of exotic femininity, as a cultural mediator and supporter of European colonialism, and as a model for assimilation and conversion.

the authenticity of the famous rescue scene has come to be doubted in contemporary scholarship. In his first account of the cultural encounter with the North American natives, John Smith narrates his captivity among the Algonquians as well as the early skirmishes between English settlers and Natives, and although he mentions Pocahontas in this early document as a messenger between Powhatan and the settlers, he does not credit her with having saved his life.

Smith thus adds this rescue scene to

his account of the initial intercultural contact in North America

almost two decades after the incident had supposedly occurred and

only after Powhatan as well as Pocahontas had died.

Task : Analysis of the 1628 painting . Interracial relations? Relate the 1622 massacre to the appearance of the rescue scene.

Smith could then, many years after Pocahontas's death, glance back at the primal scene of intercultural encounter nostalgically and present her as a model: In fact, throughout the 18th century historical accounts blame Native American resistance to intermarriage and reluctance to mingle more intimately and on a broader scale with the English for the continuously deteriorating English-Native relations. Another problem facing the colony in its early years was the high number of settlers who left the English settlement in order to live with the Natives and who were "rapidly and unproblematically assimilated" thus undermining any ideological construction of English superiority. Indigenization of the English, i.e. 'going native' was a common phenomenon and posed a threat to the very existence of the colony not least by harming promotional efforts in England geared toward attracting more people to settle in Virginia.

Therefore, the story of Pocahontas came in handy for those advocating colonization and was widely used in the promotional literature encouraging further immigration from England. While the trend of 'going native' among the English settlers was hushed up, the Pocahontas tale at the same time was ideologically exploited as it advertised Native American acceptance of the superiority of the English culture.The Pocahontas narrative "has come to validate in the national psyche the presence by a mythical indigenous consent of Europeans in America" by playing off Pocahontas as the "exotic peacekeeper" against the rest of the Natives as "bloodthirsty savages".

During his stay with his wife and son

in England, John Rolfe writes his own promotional tract to satisfy sponsors of the colony.

While his marriage "symbolized an uneasy truce" in English-Native relations. Throughout the second half of the 17th century and

the 18th century Pocahontas and John Rolfe figured as "the great

archetype of Indian-white conjugal union". At

the same time, however, Virginia was the first colony to introduce

anti-miscegenation laws: in 1662, the legislature passed the Racial

Integrity Act to prohibit the intermarriage of whites and blacks as

well as whites and Natives. And still, Pocahontas and John Rolfe

continued to be seen as foundational figures and as a blueprint for

an alternative version of what American race relations could have

been. The solution of racial conflict and

territorial disputes via intermarriage and miscegenation seemed less

and less feasible.

Following American independence, Pocahontas attained her iconic mythical status in American culture and literature. The utopia of interracial love that was symbolized by the Pocahontas figure develops into a myth of the past while at the same time the policy of 'Indian removal' is implemented and carried out.

It is in the age of Indian removal -

an official policy of deportation resulting in the death of thousands

of Native Americans on the Trail of Tears - that Pocahontas becomes

a full-fledged American icon and myth. In order to mythologize

Pocahontas in the context of profound anti-Native sentiments, a

number of discursive strategies had to be employed:

First of all,

most texts and visual representations cast Pocahontas as the savior

of John Smith rather than as the wife of John Rolfe; the second part

of the narrative becomes lastingly marginalized in order to avoid the

issue of miscegenation - by then an even stronger cultural taboo

than in the 17th century. Second, Pocahontas figures somewhat

nostalgically as a heroine of the past and of an innocent American

beginning. The split between "the peace-loving and Christian

Pocahontas" on the one hand and her

allegedly treacherous, violent and uncompromising indigenous male

counterparts on the other is continued and deepened. This profound

feminization of the narrative avoided the contradictions between

racial discourse and foundational mythmaking. Third, the Pocahontas

narrative underwent a turn to sentimentalism that further diverts

attention from the brutality of colonial politics and that champions

her as a romantic symbol of voluntary cultural contact and

self-chosen assimilation to the white culture.

Although his book is, strictly speaking, a travel report, Davis presents us here with the first fictionalized treatment of the topic; akin to a short story, the narrative displays markers of fictionality rather than an investment in historicism . Davis expands on the Pocahontas story and is credited by many scholars with the fabrication of the love story between Pocahontas and John Smith, a young girl and an older man by 17th-century standards. The manner in which he processed the story can be sensed from the following excerpt, a scene that follows upon Pocahontas bringing food to Smith and the Jamestown settlers:

The acclamations of the crowd affected to tears the sensibility of Pocahontas; but her native modesty was abashed; and it was with delight that she obeyed the invitation of Captain Smith to wander with him, remote from vulgar curiosity, along the banks of the river. It was then she gave loose to all the tumultuous ectasy of love; hanging on his arm and weeping with an eloquence more powerful than words.

Task : reflect upon the tone.

While we may glimpse from this paragraph why Davis's sentimentalist narrative never became canonical, we cannot overestimate the cultural work his texts performed in the context of an American foundational ideology: he "unearthed" the story of Pocahontas; he popularized and perpetuated it; but most of all, he romanticized it and made historical fiction of it

The so-called Indian plays of the 19th

century popularized stories about Pocahontas and similar, fictive

figures in a mode of retrospective nostalgia. The Indian hero or

heroine is cast as a melancholic figure, doomed to disappear with the

advance of 'civilization;' Pocahontas's assimilation into white

culture and the trope of the vanishing Indian thus were two dominant

modes of representing this disappearance.

Throughout the 19th century, Pocahontas

plays abounded the play in

1830. it also coincided with the Indian Removal Act, which the US

Congress passed in the same year. Overall, the seeming paradox

between the policy of Indian removal and the popularity of the Indian

plays is compelling.

Task : Account for the paradox. Why such appropriation?

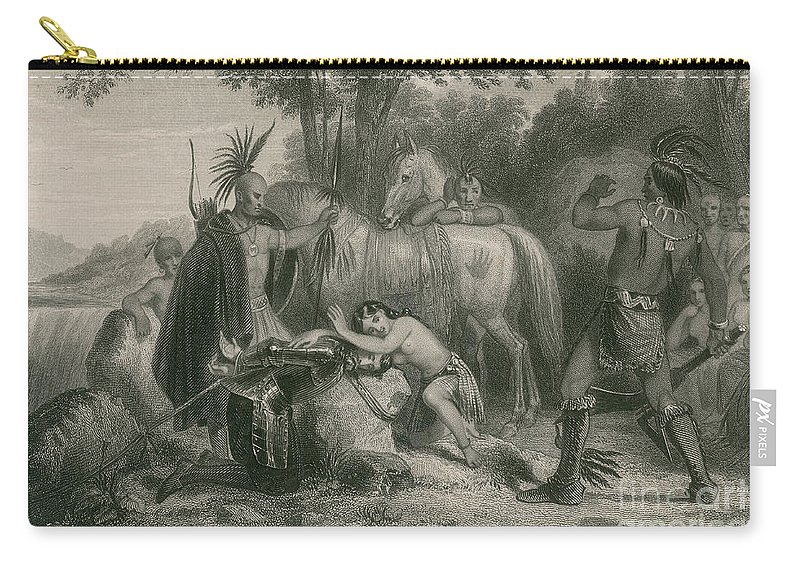

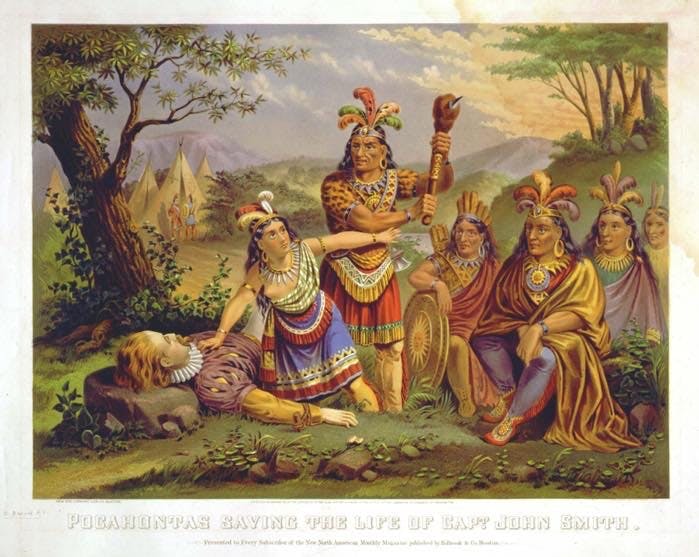

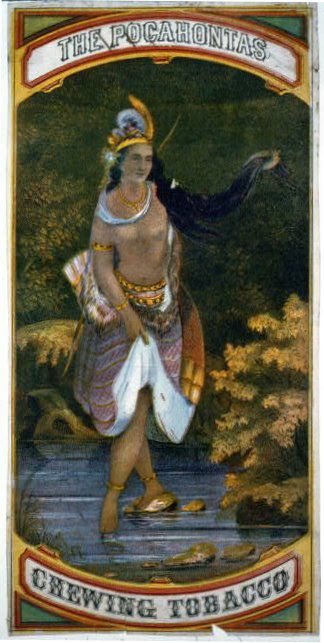

In the 19th century many painters tried to visualize this crucial moment in early American history - a moment without which, it was assumed, there would not have been any American history to begin with. These visual representations of Pocahontas range from exoticist/primitivist to classicist, either depicting her as a nude female Native or as a (to all appearances) white young woman.

The most famous portrait of Pocahontas is probably the 1616 "Matoaka, alias Rebecca" copperplate by Simon van de Passe, which depicts her as an English lady . This portrait is heavily stylized - there is no trace of the Native woman, not even in her features - and follows contemporary conventions of court portraiture in order to affirm the new Christian identity of Powhatan's daughter as well as her noble background.

In the United States, the memorial culture centering on Pocahontas in the 19th century produced several works of art that particularly in terms of their location are highly important. One of them would be the 1825 relief by Antonio Capellano which is located over the west door of the rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, D.C.: "Its inclusion in the Capitol at this early date makes clear that the rescue of Smith by Pocahontas had long been perceived as a crucial generative moment in the history of the United States". In 1825, Americans had already adopted Pocahontas as a figure of national consensus.

John Gadsby Chapman, The Baptism of Pocahontas (1839).

One of the most famous images produced

in the 19th century, however, one which also inscribes Pocahontas

into American cultural memory and whose importance cannot be stressed

enough, is the painting of Pocahontas's baptism by John G. Chapman

(1839), which is exhibited in the rotunda of the US Capitol, at the 'heart of the nation.'

Task and questions : why such representation there? de-indigenization?

This painting is remarkable in many ways. First of all, for its topic: it is not the famous rescue scene with John Smith, nor her marriage to John Rolfe, nor Pocahontas and her son, the offspring of this remarkable intercultural union, that we find depicted here; rather the painting shows Pocahontas's baptism, "shrewdly choosing the moment when European ritual symbolized her rejection of her own culture and her incorporation into the ranks of the saved".

"Pocahontas is lighter in skin tone than the other

Indians in the painting. [...] This conventional depiction allows

Chapman to suggest that a blanching of any distinctively Indian

racial features has occurred through this Christianization process". Her pose is reminiscent of the kneeling Virgin Mary

found in nativity scenes. Also, she has her back

turned to the other Natives, who are traditionally clad; her white

gown, by contrast, symbolizes virginity, innocence, and rebirth.The baptism scene most crucially

displays the ideological twist and the central paradox in the making

of the Pocahontas myth. Whereas she is seen as the Native 'other,'

her baptism constitutes - in the way Chapman portrays it, at any

rate - a forceful ritual of de-indigenization.

While Pocahontas was claimed in the 19th century as the "first mythic Indian" and enthroned as a national heroic figure, she was also claimed in the name of many other agendas.

we have to acknowledge that the attempts at discrediting the Pocahontas narrative on the part of many Northerners during the years of national crisis failed, as by that time "the name and the accomplishments of the Indian princess Pocahontas were deeply ingrained in the collective American consciousness. By the second half of the nineteenth-century, her heroic identity was far beyond the scope of any such attempts at demythologization"

In a quite different vein, Pocahontas has been cast as an early American feminist. Mary Hays's 1803 Female Biography depicted Pocahontas as a model woman, as a "princess politician" and as a manifestation of "nineteenth-century resolute womanhood". In varying versions, her story has been offered as a narrative of empowerment for women, investing her with a specifically female agency in a patriarchal context of male saber-rattling.

The dissemination of the idea and trope of the 'new woman' coincided with the search for a usable feminist past. While women were campaigning for their right to vote in the US (granted in 1920 by the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution), Pocahontas was featured in a number of plays and poems that used her as a model feminist.

US Postal Service, Pocahontas 5¢ (1907).

Whether prototypically feminine or feminist, Pocahontas is not only claimed as a founding mother by female ethnic writers but throughout also remains a national symbol, as evidenced by the 5-cent stamp that comes out in 1907 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia. There is, thirdly, a full-fledged Pocahontas cult after World War I among a group of American modernist writers, who also discover her as an American 'founding mother' and as a central emblem of American indigenous traditions to be contrasted with European traditions.

There is not one single homogenous Native American response to the multi-layered 'white' mythologization of Pocahontas. Many contemporary Native American writers have tried to imagine what Pocahontas could or might have thought or said as we simply do not have any records. The Native American poet Paula Gunn Allen has given a voice to Pocahontas in one of her poems titled "Pocahontas to Her English Husband, John Rolfe," in which the speaker reminisces:

Had I not cradled you in my arms Oh beloved perfidious one, You would have died. And how many times did I pluck you From certain death in the wilderness - My world through which you stumbled as though blind? [...] Still you survived, oh my fair husband, And brought them gold Wrung from a harvest I taught you To plant. Tobacco. [...] I'm sure You wondered at my silence, saying I was A simple wanton, a savage maid, Dusky daughter of heathen sires Who cartwheeled naked through the muddy towns Who would learn the ways of grace only By your firm guidance, through Your husbandly rule: No doubt, no doubt. I spoke little, you said. And you listened less [...] I saw you well I understood your ploys and still Protected you, going so far as to die In your keeping - a wasting, Putrefying Christian death - and you, Deceiver, whiteman, father of my son, Survived, reaping wealth greater Than you had ever dreamed From what I taught you and from the wasting of my bones.

Tasks and questions : the other in the poem? A Native American perspective?

The poem does not recreate the conventional topoi of modesty and submission, nor does it describe a harmonious and passionate union - rather it constructs a stance of superiority on the part of Pocahontas vis-à-vis her husband John Rolfe. Referring to the strategies of colonial othering, the speaker reverses well-known stereotypes: it is he who is 'the other' - ignorant, childlike, helpless, and dependent; it is she who rescues him not once, but many times; and yet, in his world/discourse she does not have a voice. Ultimately, she holds him responsible for her death, which is intricately connected to his acquisition of fame and fortune.

From a Native American perspective, the story of Pocahontas is not a story of conversion, assimilation, and sacrifice, but a story of Native survival. Pocahontas not only survived the first contact but delivered a child that may be seen as the beginning of an alternative "crossblood" American genealogy

Responding both to white colonial mythmaking and to the marginalization of women within Native American studies, Paula Gunn Allen suggests "putting women [like Pocahontas] at the center of the tribal universe" in order to "recover[] the feminine in American Indian Traditions"

Tasks and questions : interpret the painter's purpose

A postcolonial perspective on the Pocahontas narrative is provided by the Caribbean-American author Michelle Cliff in her novel No Telephone to Heaven (1987).

Cliff's narrator tries to de-allegorize and demythologize the figure of Pocahontas, to come to her 'face to face' and to see her as another human being. Downsizing the myth in favor of the individual is a strategy that many contemporary authors have employed.In spite of Native American criticism and controversies about her status as a foundational American heroine, the figure of Pocahontas is very much alive in American popular and mass culture, and romance continues to be the central paradigm of her narrativization

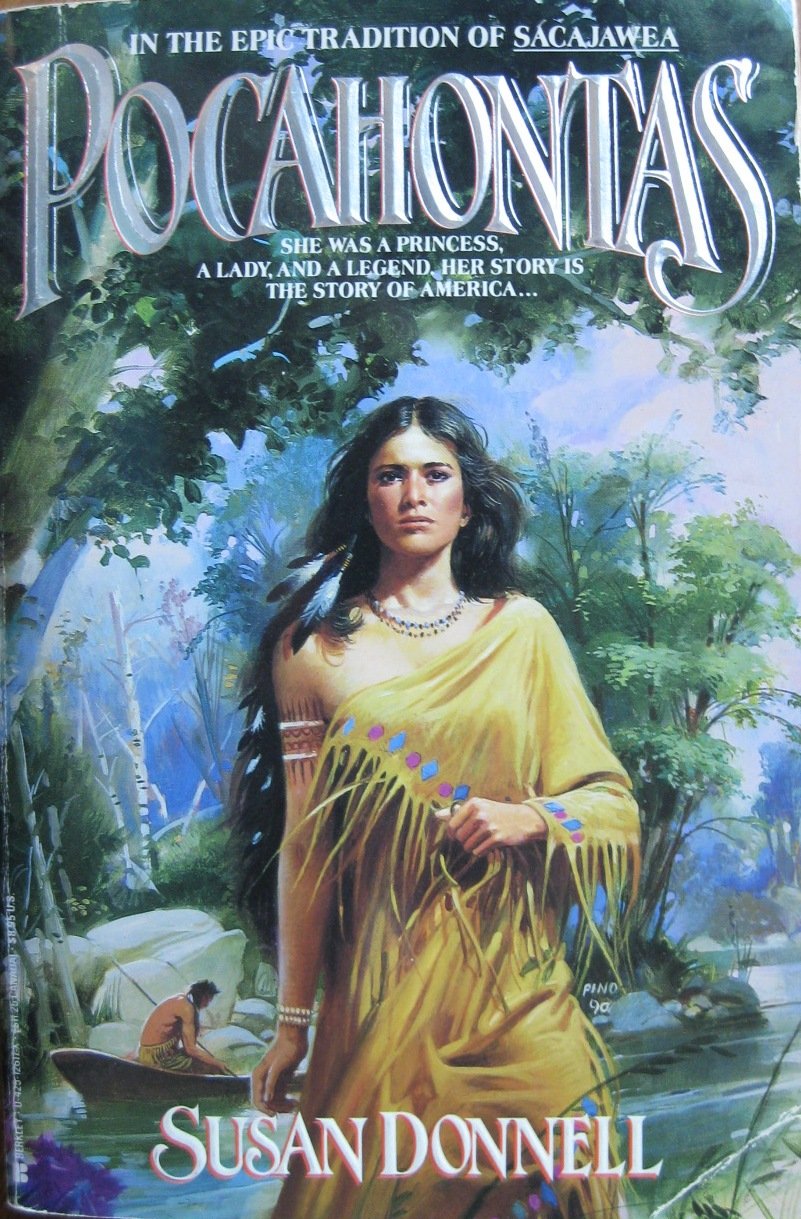

Cover of Pocahontas by S. Donnell

(Berkley Books, 1991).

Task and questions : What does the cover tell about the narrative? The genre? Stereotypes?

Popular Pocahontas narratives operate

with the romance formula when representing Pocahontas as saving John

Smith out of love. The rescue scene dramatizes the conventional 'love

is stronger than death' topos as well as the notion of sacrificial

love, i.e. love as selfless altruism that makes one willing to give

one's life so that the other's may be spared. In the Pocahontas

narrative, this "fantasy of the all-sufficiency of love"overcomes linguistic barriers as well as cultural difference -

and, needless to say, does away with all questions of colonial power

relations. Pocahontas is completely

de-indigenized on the cover of Donnell's book, apart from her dress

and three feathers in her black hair, which are stereotypical

attributes in Western depictions of indigenous attire.

This strategy of de-indigenizing Pocahontas - which we have already found at work in many 19th-century representations - was continued most prominently in our era of late capitalism by a cultural production that brought new and unprecedented fame to the old legend: Walt Disney's Pocahontas (1995). This animated motion picture started a veritable Pocahontas craze fuelled by "a $125 million marketing blitz".

Task and questions : possible criticisms?

The Disney film has been viewed positively as a balanced, politically correct representation of first contact in North America, even as "the single finest work ever done on American Indians by Hollywood", but it has also been criticized as another romantic fantasy about 'Indians' glossing over a history of genocide and dispossession, and thus, as romanticizing colonialism.

After a friendship has formed and Pocahontas has rescued Smith from execution, the film includes a second rescue scene in which Smith takes a bullet for Powhatan; seriously injured, Smith has to return to England to recover, thereby providing the plot with a rationale to separate him from his beloved Pocahontas. This narrative maneuver "displaces actual miscegenation from the narrative frame", which the film also does by omitting Pocahontas's relationship with John Rolfe. The story is awkwardly sanitized: there is no mention of Pocahontas's captivity or the eruption of violence in white-Native relations. The possibility of Europe and America coming together in a peaceful encounter leading to friendship and love rather than to war and genocide is a fantasy people still like to entertain.

the longevity of the Pocahontas narrative in US-American culture has been evidenced by James Cameron's Avatar (2009), a science-fiction version of the Pocahontas story with an anti-colonialist agenda. The film's white hero is rescued twice by the Native Pocahontas character: the first time she helps him to survive in the 'wilderness' of the fictive moon of Pandora, the second time she rescues him from his fellow colonizers. In the end, it is he who becomes completely and irrevocably indigenized, rather than her being de-indigenized

The military-industrial, (neo-)colonial enterprise from earth is successfully thwarted on Pandora - to stay with the analogy: the Jamestown on Pandora is wiped out. Cameron's blockbuster may at first glance be conventional in its enactment of intercultural romance and admittedly celebrates indigenous traditions that are accessible only through the most advanced technology , yet its insistence on the indigenization of the hero from earth into Pandora's Na'vi culture constitutes a powerful critique of US American neoimperialism.

Cameron's film combines a refashioning of the Pocahontas story with a criticism of US-American military interventionism as part of an interracial love story between a man from earth and a Pandoran woman. With the Pocahontas myth in mind, we can read Avatar as a comment on a core foundational American myth in the age of globalization.

Having traced the Pocahontas myth through several centuries of US-American history and culture, we find the strategy of de-indigenization intricately intertwined with that of de-politicization.Even though Pocahontas may appear as only "half-raced" in versions of the myth that de-indigenize her, assimilate her, and claim her as a convert to Christianity and Western ways, as a figure in colonial and colonizing plots she is nonetheless "fully sexed", i.e. sexualized and eroticized according to Western standards of 'exotic beauty.' On the other hand, as Indian princess and female noble savage, Pocahontas is one of the most prominent and most ubiquitous female figures in American children's books and to this day is one of the most popular Halloween costumes for girls.