THE MYTH OF THE SELF-MADE MAN

Besides notions of religious predestination, political liberty, and social harmony, the imagined economic promises of the 'new world' constitute another important dimension of American exceptionalism and US foundational mythology. The popular phrase 'rags to riches' describes social mobility in analogy to geographical mobility in the discourse of westward expansion, the difference being that the latter refers to horizontal and the former to vertical mobility. Historically, the notion that upward mobility in US society is unlimited regardless of inherited social and financial status has been used to contrast the US to European societies with rigidly stratified social hierarchies, and to support the claim that the American economic system leads to a higher standard of living in general as well as to a higher degree of individual agency and economic opportunity

In its hegemonic version, the myth of

the self-made man refers, first of all, to expressive individualism

and individual success and describes a cultural type that is often

seen as an "American invention" and a "unique national product". Based on the assumption of competitive

equality, the self-made man has often been connected to utopian

visions of a classless society, or at least to a society that allows

considerable social mobility.

The culturally specific figure and formula of the self-made man thrives according to all empirical evidence on the illusion that the exception is the rule and thus follows and time and again re-inscribes a social Darwinist logic based on the quasi-natural selection of those fit to compete and succeed in a modern "post-stratificatory society"

The national type of the self-made man and the creed of American mobility imply "parity in competition", and, in fact, "an endless race open to all" despite the fact that not all start out even or compete on an equal footing, and have been used to bolster the assumption that there are no permanent classes in US society. In "the doctrine of the open race", the providential success of the self-made man was identified with the success of the national project, and expressive individualism was thus regarded not only as the basis for individual but also for collective success.

In many ways, the notion that individuals can determine their own future and change their lives for the better is a modern idea and presupposes modern notions of culture, society, and the individual along the lines of Immanuel Kant's enlightenment dictum that man will be 'what he makes of himself' which later, in Sartre's reformulation, becomes "[m]an is nothing else but what he makes of himself". This notion is the result of large-scale and complex processes of secularization that are quite at odds with Christian ethics, as it often flaunts competition, self-help, and ambition as its driving forces. This connection - or rather disjunction - of ethics, ambition, and success plays out in culturally specific ways. In the present context, the idea of personal success is closely linked to processes of nation-building. The "pursuit of happiness" (as famously formulated in the Declaration of Independence) and the "promise of American life" in their early exceptionalist logic transfer notions of happiness from the afterlife to one's earthly existence, i.e. to the present moment or at least the near future. Coupled with the Calvinist work ethic, the pursuit of happiness constructs the modern individual's path to happiness as the pursuit of property and allows for self-realization in new ways.

This notion has already been at the center of 18th-century 'new world' promotional literature, which touted America as an earthly paradise. The self-made man as a foundational mythical figure personifies this promotional discourse, and has been used to allegorize the 'new world' social order since the late 18th and throughout the 19th century. Of course, this perspective is highly biased: the eighteenth-century enlightenment subject was conceptualized as white and male, and thus the myth of the self-made man historically applies to white men only; however, we will also look at the ways in which this perspective has been revised or amended by other individuals and groups who have appropriated this myth

The coinage of the term "self-made

man" is commonly credited to Henry Clay, who wrote in 1832:

"In Kentucky, almost every manufactory known to me is in the hands of enterprising self-made men, who have whatever wealth they possess by patient and diligent labor" .

The term can thus

be considered as yet another neologism of the early republic that

speaks to specifically US-American cultural and economic patterns and

is deeply intertwined with various aspects of American

exceptionalism. There are contradictory forces at work in this

notion, as it includes both aspects of self-denial (education, hard

work, and discipline) and self-realization based on an ethic of

self-interest that aims at the sheer accumulation of

property, recognition, prestige, and personal gain without any

concern for others.

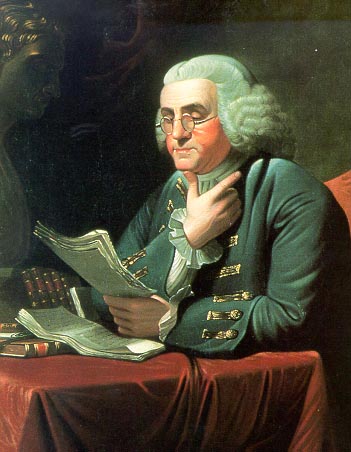

Franklin's self-fashioning celebrates individualism and free will against a deterministic social order, but it also affirms that everyone is responsible for their own fate and success in life: self-improvement and self-perfectability loom large in his texts, which were and still are part of US school curricula.

Franklin's audiences past and present read his ideas about the synergetic fusion of a paling Protestant religiosity (Franklin was a deist) and a Calvinist work ethic as enabling and fuelling a capitalist economy that promises individual and collective gain and well-being - the defense of capitalism is, time and again, the tacit subtext of the narratives of self-made men, the "spirit of capitalism". This spirit - which Weber identifies in the North American colonies as early as 1632 is brought forth by Puritanism as well as by the economic development of the colonies, which together turned people into economic subjects on the basis of an increasingly secularized logic of work-discipline, which, however, still took material wealth as a sign of God's blessing. Over time, though, success was less and less defined in religious terms, and instead became a kind of 'sublime' of the social world, a way of distinguishing one's self.

By the mid-19th century, the "ideology of mobility" was firmly entrenched in American society; it was the theme of "[e]ditorials, news stories, political speeches, commencement addresses, sermons, [and] popular fiction". Representations of the self-made man in popular fiction are particularly prominent in this period in the oeuvre of Horatio Alger, who was not only a prolific writer but also worked as an editor, teacher, and pastor. The American Heritage Dictionary defines Horatio Alger as the author of popular fiction about "impoverished boys who through hard work and virtue achieve great wealth and respect"; often living with a single mother who depends on him for support, Alger's typical protagonist usually has a chance encounter with a gentleman, who becomes his mentor as the young protagonist shows his moral integrity, works hard, and thus appears to be deserving of help. At the end of the story, he ends up comfortably ensconced in middleclass America and "is established in a secure white-collar position, either as a clerk with the promise of a junior partnership or as a junior member of a successful mercantile establishment"

Alger's novels pursue a thinly veiled didactic aim while they also cater to sensationalism, sentimentalism, and voyeurism. In the 19th century, the virtual "cult of the selfmade man" was certainly propelled and reinforced by "Algerism," as the popularity of the Horatio Alger stories came to be described, and even if his texts are hardly read anymore, Alger is still a household name today. Addressing a young, male audience, Alger's 135 books, among them the well-known Ragged Dick series which comprises six novels, have sold more than 300.000.000 copies. They "have structured national discourse as a narrative of personal initiative, enterprise, financial responsibility, thrift, equal opportunity, hard-work ethic, education and self-education, and other similar values of Puritan-Calvinist and liberal extraction" in seeming opposition to - yet ultimately in conjunction with - the so-called "bad boy-books" by Mark Twain and others that focused on a nostalgic "figurative escape into the pastoral, imaginative life of a premodern, anticapitalist world, while also embodying the enterprising and unsentimental agency of the capitalist himself". In the 19th century, Alger's books functioned as national allegories, since their adolescent protagonists' rites of passage could be paralleled with the young republic's struggle for independence. Alger's success as a writer diminished towards the end of his life, when his books became the object of criticism by an 'anti-Alger movement' which rallied to have his books removed from public libraries because they were deemed too trivial, "harmful," and "bad," and to cause a "softening [of] the brain". Alger's stories became truly iconic in the first half of the 20th century, when the sales of his books, which were then used to identify the 'American way of life' in contrast to the 'un-American' notions of socialism and communism, rose sharply; 'Cold War' ideology thus enlisted Alger as "a patriotic defender of the social and political status quo and erstwhile advocate of laissez-faire capitalism". It is during these decades that Algerism had its heyday. As Algerism came to signify "Americanism," in many crucial ways "[t]he word of Alger excluded the word of Marx".

Alger's typical protagonist has "an astounding propensity for chance encounters with benevolent and useful friends, and his success is largely due to their patronage and assistance"; this reliance on "magical outside assistance" has led scholars to describe Alger's famous hero Ragged Dick as a "male Cinderella-character in a postbellum America". Second, the protagonists of Alger's tales never become spectacularly rich or successful - they rise from poverty to a comfortable middle-class status but never beyond that, and thus do not follow the get-rich-quick formula; in fact, we may consider the rather nostalgic hankering after a "return to the age of innocence" that can be discerned in Alger's texts as indicative of his critical attitude toward "the greed of the Gilded Age", the large-scale "incorporation of America", and the new mythology of "corporate individualism". Yet, there are a number of issues that Horatio Alger stories evade, and these evasions carry ideological weight: Alger's virtuous and deserving heroes never experience bad luck and are never threatened by downward mobility - they never become homeless tramps or drifters, or inhabit any other seriously stigmatized and disadvantaged social space; as they also typically strive for white-collar employment, the factory and the "factory system" as a locus of labor is effaced altogether, and their success in the corporate world seems to be based solely on personal virtue and ambition:

"Serve your employer well, learn business as rapidly as possible, don't fall into bad habits, and you'll get on"

Yet, this corporate world is at times also cast in a negative light: "The popular image of the business world held unresolved tensions; on the one hand, it seemed the field of just rewards, on the other, a realm of questionable motives and unbridled appetites"; thus Alger's stories point to a fundamental conflict in the American experience which is vicariously solved in these narratives even if they hardly ever address it directly. Alger's stories moreover pay no attention to how class distinctions can be maintained more subtly through manners and habitus, and how the lack of a particular habitus can prevent upward mobility.

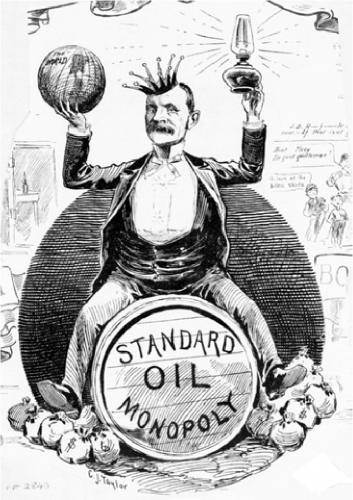

it is in the 1850s that newsboys and bootblacks become common figures in popular literature. Yet, it is Alger among all self-help propagandists who lastingly shaped the cultural imaginary of Americans by adding to Franklin's advice register a new success formula with sentimental, affective appeal which celebrated "the pleasures of property", even more thoroughly 'Giving away' one's wealth, of course, retrospectively affirms once more that one had earned and owned it legitimately. Charity thus seeks to close the gap between self-interest and the common good by 'returning' to the general public what had previously been extracted from it through often exploitative practices. In similar fashion to Carnegie, the Rockefeller family is linked to both ruthless business practices and philanthropy

C.J. Taylor, King of the World (n.d).

The myth of the self-made man - with a story based on trust in the incentives of the capitalist market, adherence to the Protestant work ethic, and luck - may be the prototypical modern American fairy tale. Decker points out how "stories of entrepreneurial success confer 'moral luck' - a secular version of divine grace - on their upwardly mobile protagonists". Success stories thus can easily be considered American fairy tales with a providential twist, and as such they echo in and are invoked by many cultural productions from 19th-century popular fiction to 20th- and 21st-century Hollywood films. Their protagonist, the self-made man, personifies the American dream as wishful thinking and wish-fulfillment at the same time.

The self-made man has not only been a figure of consensus but also one of controversy and criticism. By expressing anxieties about the overthrow of established social hierarchies, offering spiritual conceptualizations of self-making, critiquing capitalism and corporatism, or warning of the fleeting nature of material wealth, all of these texts point to the precariousness of dominant white, masculinist, and individualist notions of self-made manhood in the US.

The American dream, as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries under the impact of mass immigration came to understand it, was neither the dream of the American Revolution - the foundation of freedom - nor the dream of the French Revolution - the liberation of man; it was, unhappily, the dream of a "promised land" where milk and honey flow. And the fact that the development of modern technology was so soon able to realize this dream beyond anyone's wildest expectation quite naturally had the effect of confirming for the dreamers that they really had come to live in the best of all possible worlds.

The notions of upward social mobility and the pursuit of the American dream have often been connected to the immigrant experience. Despite the fact that stories in the Horatio Alger vein at times displayed a nativist streak, immigrant authors too used the narrative formula popularized by Alger to frame the topics of immigration and Americanization in the context of individual success and self-making. Beginning a new life in the US in these texts is represented as a process of (predominantly cultural) change and transformation, and is rendered in the same civil religious diction that also shapes many discussions of the melting pot. However, even if immigrants often comment on the fact that the standard of living in the US is higher than in their countries of origin, they have no illusions as to the hierarchies that structure US society, even if these hierarchies may be relatively permeable.

The first consists of success narratives that mostly conclude with a happy ending and feature successful and well-adjusted (i.e. assimilated) protagonists that take pride in their own achievements in a society which is usually described as rewarding hard work, discipline, and stamina

To summarize, immigrant voices and stories of the type outlined above articulate the hegemonic version of the myth of the self-made man and affirm exceptionalist notions of the US as a society in which anyone can achieve success through individual talent, hard work, and discipline.

The second type of immigrant tales in contrast is less unequivocally committed to the American success mythology, and consists of narratives of upward mobility that end on not quite so happy a note or consider the downside of success - in fact, outward success may even be paired with a sense of failure, loss, and alienation

This discrepancy becomes evident, for instance, in Abraham Cahan's The Rise of David Levinsky (1917)

Scholars have pointed out that many of

those immigrant narratives critical of the success myth were written

in languages other than English even as they were printed in the US.

Werner Sollors (cf. Multilingual America), Orm Øverland (cf.

Immigrant Minds), and others have pointed to the connection between

multilingualism and non-conformity in American literature, and Karen

Majewski's reading of Polish-language immigrant writings by Alfons Chrostowski (e.g. "The

Polish Slave"), Bronislaw Wrotnowski, and Helena Stas (e.g. "In

the Human Market: A Polish-American Sketch") also points to this

connection. Often written in a

naturalist mode, these narratives, of which some were recorded and

fictionalized by Progressivist reformers, naturalist writers, and

so-called muckraking journalists, are part of a discourse of failure

that is situated at a distance from notions of American civil

religion, patriotism, and exceptionalism.

The slums of New York City, where much of the immigrant population lived at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, have been famously captured by Danish American journalist and photographer Jacob Riis in his book How the Other Half Lives (1890). Similarly, Stephan Thernstrom chronicles the lives of those who are at the bottom of society in his The Other Bostonians (1973). Many American critics of the selfmade myth in and around what Daniel Bell has described as "the 'golden age' of American socialism" - the years from 1902 to 1912 - had other ideas than laissez-faire capitalism for realizing a truly egalitarian society

Narratives of immigrant failure thus are obviously at odds with the hegemonic version of the self-made man and expose the underside of the myth. They also reveal the myth's often unacknowledged social Darwinist underpinnings, as the myth's hegemonic version shrugs off the fact that it is not success and self-making but sheer survival that is at stake for many immigrants in a society that is characterized by gross class inequities.

A fourth kind of formula explores alternative modes of self-making and success that often transgress the bounds of legality, and thus also do not follow the dominant version of the success myth. These narratives acknowledge the difficulties of immigrant life in the US that arise from nativist resentments and other forms of discrimination against immigrants that often make assimilation impossible or undesirable, and thus locate success not within the American mainstream but in family- or ethnically-based criminal organizations and in plots revolving around a central gangster figure. A prominent example of this kind of tale is the Godfather saga (cf. Mario Puzo's novel and Francis Ford Coppola's film of the same title, as well as the sequels they spawned), which exemplifies an immigrant success formula based on maneuvering at the limits of (and beyond) legality and in socio-economic niches. In fact, as John Cawelti already argued in the 1970s, we find "a new mythology of crime" that reveals a fascination with power and corruption; this fascination, however, may be explained not only by the allure of glamorized depictions of organized crime but also by the fact that organized crime in many ways reflects rather than contrasts with what often hardly deserves to be called 'honest' business in the US: Daniel Bell argues that "organized crime resembles the kind of ruthless business enterprise which successful Americans have always carried on"; thus, "[t]he drama of the criminal gang has become a kind of allegory of the corporation and the corporate society" which conveys "the dark message that America is a society of criminals". Seen in this light, immigrant gangs and robber barons may be more closely connected than is immediately evident. More recently, the Godfather formula was taken up in the television series The Sopranos (1999-2007) as well as by a host of other series who focus on the self-making of characters conventionally thought of as 'criminals.' Beside Italian American mafia dynasties, Irish Americans also figure prominently in this alternative success myth, for example in Martin Scorsese's Gangs of New York (2002), which dramatizes nativist and Irish gang life against the backdrop of the New York Draft Riots of 1863 and other contemporaneous historical events. The four different 'success' patterns that we can detect in representations of the immigrant experience thus cover a broad spectrum of responses to the myth of the self-made man: affirmative ones that tend to mimic older rags-to-riches narratives; mildly affirmative ones that often substitute material gain with nonmaterial notions of success; highly critical ones that mostly focus on failure (caused by adverse circumstances and discrimination) rather than success; and mildly critical ones that sidestep the legal framework of the success myth but champion material success nonetheless. In all of these versions, the self-made man (or woman) appears as a more or less contested prototype of American entrepreneurship, whereas social stratification and systemic inequality are more systematically addressed only selectively by writers and critics who are invested in a socialist agenda that often does not stop at national borders and thus more fundamentally critiques the myth of the self-made man along with notions of American exceptionalism.

As the self-made man has been such a

prominent figure of empowerment, emancipation, self-reliance, and

autonomy in the American cultural imagination, it is perhaps not

surprising that African American writers and intellectuals took up

the image as well as its cultural scripts of success and appropriated

them for their own ends. In this section, I will thus trace the

critical as well as affirmative responses to the powerful cultural

prototype of the self-made man that can be found in African American

cultural criticism, literature, and popular culture from Frederick

Douglass to Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama.

Frederick Douglass (1817/18-1895) for instance documents in his autobiography his own process of emancipation in a way that strongly resonates with the myth of the self-made man.

"[m]y life had its beginning in the midst of the most miserable, desolate, and discouraging surroundings" (Up from 15) and ends with Washington's account of being awarded an honorary degree from Harvard University in 1896 (he is also invited to dine at the White House by US president Theodore Roosevelt in 1901)

Alice Walker's epistolary novel The Color Purple (1982), which narrates the story of two sisters, Celie and Nettie; even if their lives are characterized by acts of the most brutal patriarchal violence, abuse, and oppression, the novel ends fairly happy, with Celie becoming a self-made woman who supports herself as a tailor and owns her own house. The novel has been criticized for both its explicit depiction of violence and sexual abuse (according to the American Library Association, it is one of the most frequently challenged books) and for its somewhat implausible, (pseudo-)emancipatory happy ending

Media personality Oprah Winfrey for instance, who grew

up in rural poverty, went on to become one of the richest self-made

women in the US, and can easily be considered to be the most

prominent icon of black female success. In her talks, she affirms

notions of expressive individualism and the myth of self-making by

once more reiterating the claims that hard work, moral integrity, and

discipline lead to material success and that experiences of crisis

and failure - rather than being indicative of larger social,

political, and economic problems - constitute chances for

self-improvement. In this sense, her philanthropy and the laudatory

discourse within and by which her philanthropic and charitable

activities are framed and promoted (not least by herself) function as

complementing and enhancing her own success myth: philanthropy and

charity become part of an entrepreneurial scheme that - not unlike

Rockefeller's and Carnegie's approach - attempts to forestall

and defuse any critique of structural injustice and inequality.

Barack Obama - whose rise to the highest political office in the US has often been rendered according to the standard narrative formula of the success myth - has also himself appropriated the myth of the self-made man in many instances, for example in the following passage from the speech he gave in Berlin on July 24, 2008:

I know that I don't look like the Americans who've previously spoken in this great city. The journey that led me here is improbable. My mother was born in the heartland of America, but my father grew up herding goats in Kenya. His father - my grandfather - was a cook, a domestic servant to the British. ("World")

Whereas Obama here appropriates the cultural script of the white success mythology to frame his own family's story (from domestic servant to US president in the course of two generations) and more generally contributes to the mythic discourse of the land of opportunity in his book The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (2006), he has also somewhat inconsistently and provocatively issued criticism of the myth of the self-made man, for instance in a speech he held in the course of his re-election campaign on July 13, 2012 in Roanoke, Virginia:

[L]ook, if you've been successful, you didn't get there on your own. You didn't get there on your own. I'm always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something - there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there. If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you've got a business - you didn't build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn't get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet. You [wealthy people] moved your goods on roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces the rest of us paid for. ("Remarks")

Even if phrases such as "this unbelievable American system" reinforce longstanding assumptions about America's exceptionality, they at the same time also emphasize the public sector and communal efforts as prerequisites for individual success, and thus counter the hegemonic version of the myth of the self-made man. Obama's speech has been denounced as a call for "massive redistribution" (Goodman, "Obama") and as "contradict[ing] the belief in American exceptionalism, that is: Laissez faire economics, equality of opportunity, individualism, and popular but limited self-government"

In sum, we can thus identify different aims for which the myth of the selfmade man has been used in African American intellectual history, culture, and individual (self)-representations, for example, to construct a positive image of black masculinity and to claim recognition for African American individual and collective achievement, but also to point to the limits of the model of expressive individualism in US society.

For one thing, self-made women are not part of the foundational narrative of self-making, and even more recent female exemplars often follow a skewed logic that tends to define female success not in terms of work as productivity, but more often in terms of the kind of work that goes into maintaining and improving one's physical attractiveness.

we may well speak of the prototype of the self-made woman as being shaped somewhat paradoxically by a process of 'othering.' Ann Douglas has diagnosed a "feminization of American Culture" as having accompanied the shift to an increasingly consumption-oriented economy in the 19th century that lastingly gendered the relations of production and consumption: The "sentimentalization" of culture "was an inevitable part of the self-evasion of a society both committed to laissez-faire industrial expansion and disturbed by its consequences. [...] [S]entimentalism provided the inevitable rationalization of the economic order"

Being interpellated not as producers/workers but as "consuming angels" by the discourse of economic wealth and social mobility which propped up the newly emergent consumer economy, women entered it as customers and as male status symbols - i.e. as passive subjects or rather objectified non-subjects - or not at all. Women's upward mobility thus depended on their relations to men: The boy in the Alger story who becomes the protégé of an older benefactor is replaced by a young, attractive girl/woman who is similarly elevated through male assistance according to a patriarchal logic in which women's function is precisely not to become independently successful but to further highlight male success by yielding to men's efforts at changing women according to their ideals.

American cultural productions also often use an Americanized version of the Cinderella tale to circumscribe female success, for example Theodore Dreiser's Sister Carrie (1901), in which the titular character, a country girl who goes on to become a successful actress, however ultimately leaves both male mentor figures with whom she has relations in the course of the novel; Anita Loos's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925), which ends with protagonist Lorelei Lee, another provincial girl, marrying into high society; or Garry Marshall's Hollywood romance Pretty Woman (1990), which tells the love story between Vivian Ward, a prostitute, and a rich businessman. Whether Carrie Meeber, Lorelei Lee, and Vivian Ward would more aptly be called self-made women, businesswomen, or "sexual entrepreneurs" is a question that cannot easily be answered. As female success often seems circumscribed by and limited to marriage as an arena in which the exchange/ circulation of social capital, economic capital, and libidinal energies is only thinly veiled by the ideology of romantic love, it is no wonder that we also encounter more critical treatments of marriage in American literature and culture, for example in Edith Wharton's House of Mirth (1905), which ends with the tragic death of protagonist Lily Bart, a young woman who refuses marriage and fails to live up to the (double) moral standards of New York high society.

From a gender-specific perspective, the Cinderella story as the (inverted) correlate of the male success myth thus defines the capital and opportunities of women differently from the capital and opportunities of men. Whereas we do find straightforward narratives of upward mobility, more often we encounter narratives of self-making that are concerned with women's outward appearance and with the work that needs to be invested in order to conform to socially defined beauty standards. Beauty contests constitute a notorious example of socially accepted cultural practices and forms of female self-making aiming at recognition, fame, and economic gain, of which the Miss America pageant is especially prominent. Invented as a marketing strategy by Atlantic City hotel owners to extend the holiday season beyond the Labor Day weekend, it took place for the first time in 1921 and, in spite of several interruptions, is still an extremely profitable venture. Ironically, 1921 was also the year women were allowed to vote in national elections for the first time, as Susan Faludi notes, which shows that emancipatory efforts conflicted and overlapped with discourses and practices that objectified and commodified women and their bodies

Overall, female self-making runs counter to the conventional American work ethic. Rita Freedman comments on the Disney television film Cinderella (1997): "Hard at work in her clogs, Cinderella was ignored. Transformed by her satins and slippers, she conquered the world". Thus, we may even speak of a somewhat perverted work ethic that encourages women to spend all their material resources and time on the exhaustive and narcissistic task of selfmanaging and self-disciplining their bodies. The fact that more and more women undergo surgical treatment before entering the Miss America contest has given rise to renewed criticism of the competition.

"[w]omen are either portrayed as material objects - little more than a collection of (often almost cartoonishly) formulaic body parts - or, equally limiting and pathological - as self-exploitative, entrepreneurial agents who are more than willing to use their bodies to 'get ahead'" or to have signs of aging or pregnancy and childbirth removed in a spirit of "responsible self-management and care"

This sort of female self-making constitutes "a liberation requiring utter submission to social authority" and complete conformity to normative gender ideals:

Performing perhaps the ultimate act of the "self-made" subject, women who undergo cosmetic surgery on these shows not only personify the exercise of political power through women's bodies, they reveal themselves as paragons of the neo-liberal doctrines of selfhelp and self-sufficiency. They are, in every way, then, "self-made women," products of the hegemonic alliance of patriarchy and global capitalism. Speaking to individualist, neo-liberal notions of empowerment, emancipation, and agency, this kind of self-making in the spirit of a "postfeminist sensibility" at the same time can also be considered as a practice which enforces conformity rather than individuality and deprives women not only of their agency, but possibly even of their lives, as made-over women, by being surgically remade again and again, ultimately may literally come undone.

Another cultural script about female self-making addresses women conventionally as wives and assigns them a supporting role in their husbands' self-making and rising in the world. In How to Help Your Husband Get Ahead in His Social and Business Life (1953), a book adhering to the prototypical "conformist sensibility of the 1950s"

Dorothy Carnegie, who tellingly refers to herself rather as Mrs. Dale Carnegie, counsels wives on how to increase their husbands' success by making them comfortable at home, boosting their egos, and - most importantly - by not pursuing careers of their own, while she herself de facto took over her ailing husband's business around the time of her book's publication. Beside patriarchal conceptualizations of female/wifely success as coextensive with the success of their husbands, there are also other - quite ambivalent - images of the self-made woman for example in cinema, in which career women are often represented negatively as deficient single females.

In the 1950s, a watershed moment for gender conservatism, movie stars like Doris Day in many films played businesswomen who give up their careers for the sake of a man, and in the 1980s, successful female professionals are also often confined to narrow stereotypes, for example in Fatal Attraction (1987), in which Alex (Glenn Close), the successful editor of a publishing company, starts terrorizing Dan (Michael Douglas) and his family after he refuses to continue their affair; Susan Faludi compellingly reads Alex's deterioration as signifying the pathologization of the businesswoman in American culture : Self-making and professional emancipation in the film's logic lead to the character's psycho-social disintegration because her career cannot compensate for her lack of a husband and family. The romantic comedy Working Girl (1988), in which we follow Tess McGill's (Melanie Griffith's) rise from secretary to successful businesswoman, represents female professional ambition and success rather positively; however, the character of Katharine Parker (Sigourney Weaver), Tess's boss, does reinforce the stereotype of the scheming and callous career woman, and as she is also Tess's major antagonist furthermore disavows any notion of female solidarity

The myth of the self-made man strongly affirms an ideology of expressive individualism as well as individual achievement and success that conceptualizes the "pursuit of happiness" as the pursuit of property. By claiming that self-making also contributes to the greater common good, hegemonic versions of this powerful myth - or fairy tale - of social mobility still very successfully obscure its role in legitimizing and perpetuating immense structural social inequalities.

In the age of global capitalism and the new social media, corporate success on a grand scale has once more become concretized and personalized in 'selfmade' individuals such as Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, or Mark Zuckerberg (again, self-made men), who are turned into celebrities and high priests of the American civil religion of success, albeit with a new global dimension

In Steve Jobs: Life Changing Lessons! Steve Jobs on How to Achieve Massive Success, Develop Powerful Leadership Skills and Unleash Your Wildest Creativity (2014), William Wyatt similarly taps into the tradition of idolizing self-made men in a quite narrow ideological framework and regardless of Apple's numerous manufacturing and tax scandals and its dubious labor policies abroad (condoning for example deplorable working conditions at its suppliers in China). In spite of somewhat critical representations of his personality and entrepreneurial strategies for example in The Social Network (2010), Mark Zuckerberg's achievement also has been much applauded in biographies and advice literature such as George Beahm's Billionaire Boy: Mark Zuckerberg in His Own Words (2013) and Lev Grossman's The Connector: How Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg Rewired Our World and Changed the Way We Live (2010). These more recent embodiments of the self-made man indicate that the myth has weathered the storms of capitalism's periodic crises and may have in fact even been instrumental in providing the ideological glue which maintains the quasi civil religious belief that upward mobility can be achieved by all.

In turn, in the logic of this myth, financial and economic crises are not considered as part and parcel of a dynamic that is built into the increasingly globalized capitalist US economic system, but as somehow random and contingent or caused by outside economic influences. Nancy Fraser has called this false attribution of responsibility for structural inequalities "misframing"; according to her argument, the intrinsic problems of a market economy are often credited to adverse outside factors allegedly skewed against the self-made man as object and agent of American exceptionalism. In view of a transnational perspective, scholars have also pointed out that many other societies are much more permissive and less socially deterministic than the US, which however has not lastingly affected specifically American notions of the self-made man and competitive equality.