THE MYTH OF THE MELTING POT

E Pluribus Unum is also engraved on the

globe at the feet of the Statue of Freedom, the classical female

allegorical figure at the top of the US Capitol dome.

It can be regarded as an unofficial motto of the United States, and has become a standard manifestation of the melting pot myth, which more than any other foundational myth evokes a vision of national unity and cohesion through participation in a harmonious, quasi-organic community that offers prospective members a second chance and a new beginning and molds them into a new 'race,' a new people.

The melting pot is a myth about the making of American society. In its dominant version, it envisions the US in a state of perpetual change and transformation that is partly assimilation, partly regeneration, and partly emergence, and emphasizes the continuous integration of difference experienced by both immigrant and longer-established sections of the population.

As imagined communities, nations not only need narratives of origin, but also narratives of their future - in the case of the US, which looked upon itself as a nation of immigrants, such a forward-looking narrative needed to address how differences of origin and descent could be transcended, and the melting pot seemed to be the perfect model to describe the particular composition of US society.

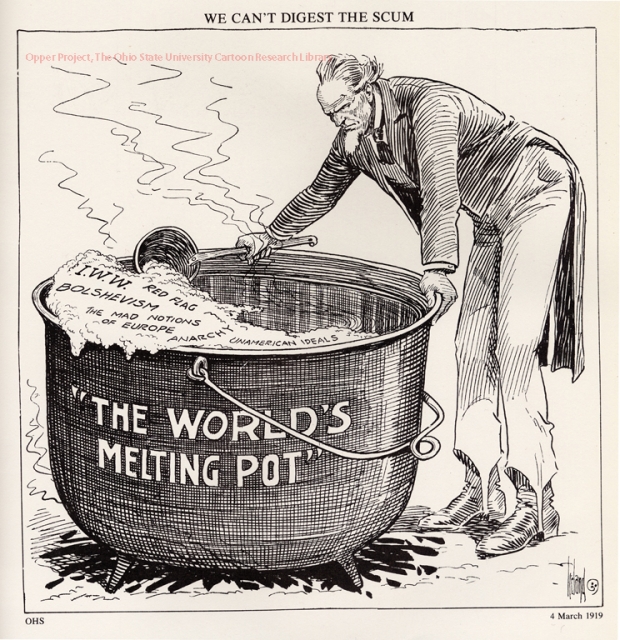

From the beginning, the melting pot has been seen as an ambiguous symbol of American unity; it has been looked upon as a myth providing cohesion and a sense of evolving Americanness on the one hand, and as an instrument of forced acculturation and violent assimilation on the other. Several questions suggest themselves when assessing this myth: Who is in the 'pot' and who is doing the 'melting'? What exactly is melted down? Which elements would prove to be resilient or dominant in the process, and with what result?

Jefferson's semantics of 'blending' comes close to 'melting' and indicates the potential he sees for a kind of 'new race,' a potential that is also expounded by other founding fathers. In fact, "several prominent southerners in the eighteenth century proclaimed intermarriage the solution to the Indian problem". However, Jefferson's utopian "vision of interracial nationhood is ambivalent as it also prefigures and accepts the dissolution of the Native Americans and their cultures through racial mixing; Today, Jefferson is seen as both "the scholarly admirer of Indian character, archaeology, and language and as the planner of cultural genocide, the architect of the removal policy, the surveyor of the Trail of Tears". When he tells the chiefs of the Upper Cherokee that "your blood will mix with ours the "only efficient scheme to civilize the Indians is to cross the breed". The notions of 'melting' and miscegenation in this melting pot design thus point to and justify what amounts to extermination policies - or what Matthew Jacobson in a different context has termed "malevolent assimilation that were part of what white colonizers liked to call their 'civilizing mission'.

Whereas we can note that "[b]y the middle of the nineteenth century it was widely accepted in America that the nation had a cosmopolitan origin and that the unifying element of American nationalism for the time being was neither a common past, nor common blood, but the American Idea" and that "[t]he motto of American nationalism - E Pluribus Unum - stresses the ideal of unity that will arise out of diversity"

I Hear America Singing

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day-at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly,Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

Following up on Bryce at the very end of the 19th century, historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861-1932) used the melting pot metaphor to describe processes of Americanization at what he refers to as the 'frontier.' In his lecture on "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," Turner suggests:

The frontier promoted the formation of a composite nationality for the American people [...]. In the crucible of the frontier the immigrants were Americanized, liberated, and fused into a mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics.

By describing the frontier melting pot as a

specifically rural phenomenon, Turner programmatically shifts the

site of Americanization from the Eastern Seaboard to the Midwest and

thus positions the West at the center of the nation. in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries, the melting pot emerged as a particularly prominent yet

controversial and often very differently accentuated model to

describe the potential effects of mass immigration.

The Melting Pot, Zangwill's best-known play, is a melodrama whose plot revolves around David Quixano, a Jewish-Russian musician who immigrates to the United States after his family has been killed in the Kishinev pogrom. In New York, he meets Vera Revendal, the daughter of wealthy Russian immigrants, who does charity work in a housing project; as their relationship progresses and they fall in love with each other, they learn that it was Vera's father who had been responsible for the brutal murder of David's family. At this point in the play, a shocked David leaves Vera, and it seems as if their budding relationship cannot overcome the trauma of the past. Zangwill's play thus has been read and canonized as a programmatic illustration and optimistic confirmation of the workings of the melting pot in American society which dramatizes the 'new world' as a place of new beginnings that discounts the individual's past and affirms that "old ethnic loyalties would diminish in the face of an inexorable process which emphasised those values that Americans held in common rather than those which kept them apart"

The melting pot is 'only a dream:'

The melting pot concept echoed in

ethnic and immigrant literature of the 1910s and 1920s, a period in

which nativist sentiments were on the rise as a reaction to mass

immigration from Europe. Yet, the concept was neither uncontested,

nor did its appropriation always occur in

the melodramatic mode of Zangwill's play. Quite the contrary: we

find a number of attempts to critique the metaphor by taking it more

or less literally.

Orm Øverland has shown how the melting pot as a symbol of assimilation was contested rather than whole-heartedly embraced in Scandinavian immigrant fiction, for example by Waldemar Ager (1869-1941), Norwegian immigrant and author of On the Way to the Melting Pot (1917), who describes the road toward assimilation as a process of loss, not of gain or liberation. Lars, the protagonist of the novel, is portrayed as assimilated and as culturally and socially impoverished at the same time.

In the face of more than 18 million immigrants entering the US between 1891 and 1920, the idea of racial and cultural amalgamation was discussed controversially by intellectuals as well as the public at large at that time. In these discussions, the melting pot concept provided a kind of middle ground between irreconcilable perspectives on the left and on the right: while liberals such as Horace Kallen and Randolph Bourne criticized the melting pot idea as a model of assimilation that led to homogenization and suggested alternative models geared toward ethno-cultural plurality and diversity instead, nativist anti-immigration critics and specifically eugenicists such as Madison Grant and Theodore Lothrop Stoddard perceived the melting pot as an imminent threat to (Anglo-) American society, welcomed the restrictive immigration legislation that curtailed large-scale immigration in 1924, and called for measures to secure the 'national health' on overtly racist grounds - proto-fascist notions of racial hygiene and racial purity are of central concern in their writings about American society.

Thus Bourne criticizes the Anglo-Saxon elite for pushing their own culture as an American leitkultur and strictly opposes assimilation, which he deems undemocratic and even inhumane. He affirms the ethnic diversity of the US and defends the tendency of immigrants to maintain ties to their countries of origin against xenophobic and nationalist sentiments that in the context of World War I (which the US would formally enter in April 1917) had been on the rise. The pressure exerted on immigrants to conform and to assimilate in these years is enormous, but many of them do not bow to these pressures. While conservative critics lament this "failure of the melting-pot," Bourne, who values cultural difference and abhors uniformity, views it positively.

Within the African American community, we can trace different reactions to the melting pot myth over time: accommodation with racial segregation and acceptance of restricted access to the American melting pot; harsh criticism of the melting pot ideology and its mechanisms of exclusion; a clear rejection of racial mixing with whites in an inverted discourse of racial supremacy based on racial pride; and, last but not least, an affirmation of a more inclusive melting pot that is explicitly multiracial and moves past the tormenting "double-consciousness" and its "two unreconciled strivings" which W.E.B. Du Bois has diagnosed for African Americans in the US .

The first position - accommodation with segregation and African Americans' exclusion from the melting pot after the Civil War - has often been associated with former slave and black intellectual Booker T. Washington (18561915). In the so-called Atlanta Compromise Speech given by Washington on September 18, 1895, he stated in regard to black and white interaction and coexistence that

"[i]n all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress".

This analogy accepts and affirms the cultural logic of racial segregation and opts for a strategy of gradualism for which Washington was sharply criticized by some of his African American contemporaries, because they considered his position to be submissive to whites and accepting of racial discrimination.

It is in the 1960s that the

(multi)cultural turn marks a shift in the perception of the melting

pot myth that subsequently tends to be lumped together with models of

assimilation of all kinds, in the process of which the melting pot

loses all of its utopian appeal because it has since been primarily

seen as a form of standardization implying the destruction of

cultural variety, and has been falsely equated with assimilation. The

advent of multiculturalism thus precluded any further discussion of

the melting pot among the cultural left.

on the one hand, and the political debate on the cultural heterogeneity of the US on the other. Multiculturalism, in its programmatic version, is positioned in clear opposition to the melting pot myth: First, like cultural pluralism, multiculturalism as a political program recognizes and seeks to retain cultural difference within the US as valuable and characteristic of a collective/ national American identity; second, it considers "monoculturalism" and ethnocentrism as repressive and coercive; third, multiculturalism engages in identity politics and calls for the representation and recognition of individuals and groups formerly underrepresented; fourth, it formulates a clear political agenda in terms of citizenship and access to society's resources (such as education) through, for instance, affirmative action programs. Multiculturalism calls for a pluralism based on an "ethic of toleration" and the primacy of "recognition". In the 1980s and beyond, discussions around multiculturalism were so polarized - especially in regard to canon debates and controversies around school curricula - that they have often been called veritable 'culture wars.'

Conservatives have denounced such initiatives as an "attack on the common American identity" and as an "ethnic revolt against the melting pot"; they thought that multiculturalism was overcritical of the US and its history and bred a "culture of complain" defined by intolerance and political correctness. Other critics in contrast suggested that "we are all multiculturalists now", since sensibilities do have changed, and quite ubiquitously, we find the rejection of the melting pot myth and assimilation policies in favor of a celebration of the diverse cultures of America's many racial and ethnic groups. As the debates around multiculturalism in American academia have ebbed, the term itself seems to have done its part: recent American studies glossaries frequently even fail to include an entry for the term multiculturalism.

The new popularity and acceptance of hyphenated identities in the context of multiculturalism encompass African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, Native American, as well as European American groups (e.g. Irish Americans, Italian Americans, and Norwegian Americans).

Whether in the context of immigrant

genealogies or mixed race identities, at the end of the 20th and the

beginning of the 21st century, ethnicity is seen largely as a way of

distinction and distinctiveness, as "a distinguishing from"

rather than as a "merging with". However, subnational

melting pot myth revisionism is somewhat polarized: For the

multiculturalists on the left, the melting pot model is unattractive

because it is perceived as "the cover for the domination of one

[group]" over others, whereas cultural

critics on the right have ironically become its most outspoken

defenders, and have celebrated it as a genuinely American invention.

Yet, contemporary critics as well as defenders of the melting pot

myth operate with a very simplistic notion that equates the melting

pot with assimilation and Anglo-Saxon conformity rather than with a

creative, continuous, and democratic process of hybridization.

Even if the melting pot already seemed to be "a closed story, an unfashionable concept, a version of repressive assimilation in the service of cultural homogenization", it has once again been revitalized in political and scholarly debates following 9/11. Reinventing the Melting Pot, an essay collection published in 2004, may serve as an example that relates the events of 9/11 directly to problems of American identity, society, politics, and culture; 9/11, according to the collection's editor, triggered intensified "soul-searching" about "what it meant to be American. Critics such as Peter Salins refer to "the need [post 9/11] to reaffirm our commitment to the American concept of assimilation" and call for "a more forthright discussion of what needs to be done to sustain e pluribus unum for the generations to come"

Developments since 9/11 have clearly

shown that US "racial nationalism" has not been laid to rest but has been merely reconfigured

to create new patterns of exclusion. Post-9/11 racism and

xenophobia clearly touch on the melting pot myth: In 2001, Gary

Gerstle predicted that "tensions with [...] Islamic fundamentalist

groups abroad, could easily generate antagonism toward [...] Muslim

Americans living in the United States, thus aiding those seeking to

sharpen the sense of American national identity".

The visions of the melting pot as a

model for American society were radical at the time they were first

articulated; as limited as they may have been in other ways, they put

into question fixed and static notions of collective American

identity as well as notions of Anglo-Saxon dominance and conformity.

The thanksgiving game with the cowboys is another insult to Native Americans in a season full of them, NBC Nov 2018

Asian Americans push for a smithsonian gallery of their own, Washington Times May 2019