The myth of the Founding Fathers

The myth of the Founding Fathers constitutes an American master narrative which has enshrined a group of statesmen and politicians of the revolutionary and post-revolutionary period as personifications of the origin of American nationhood, republicanism, and democratic culture

The term 'Fathers' suggests

tradition, legitimacy, and paternity and creates an allegory of

family and affiliation that affirms the union and the cohesion of the

new nation. When the colonists in the revolutionary decade argued

that they were no longer subjects of the British King and that they

could now govern themselves (cf. Declaration of Independence).

The Founding Fathers denote a secular myth that in its hegemonic version claims that the US evolved from the Puritans' Mayflower Compact to the political maturity of republicanism. It also constitutes a myth of a new beginning effected through a revolution

The myth of the Founding Fathers focuses on a group of historical actors; it symbolizes cooperation and interdependence by toning down internal conflicts among those actors and by erasing their local and regional interests, etc. It also strongly personalizes the origins of American nationhood, republicanism, and democracy by presenting them as the results of the political genius, virtue, and audacity of extraordinary individuals.

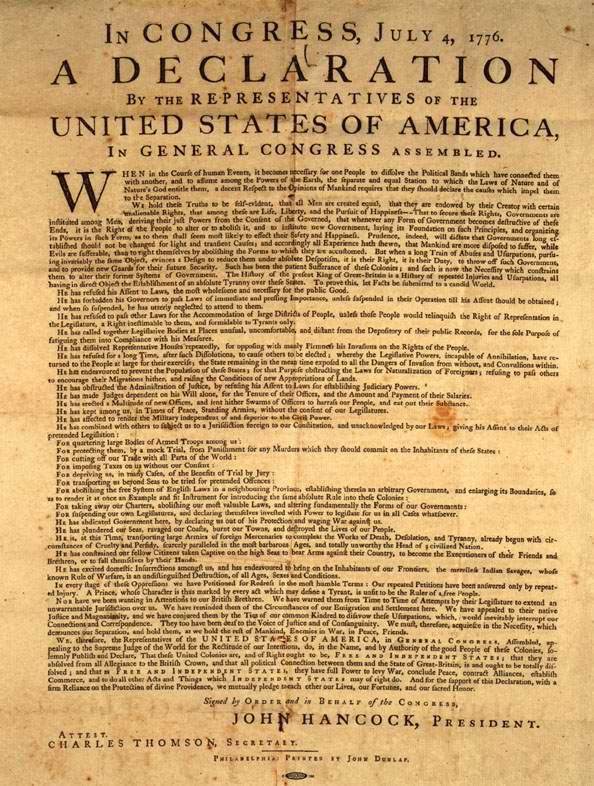

Technically, the Founding Fathers were the delegates of the Thirteen Colonies who signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and later the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

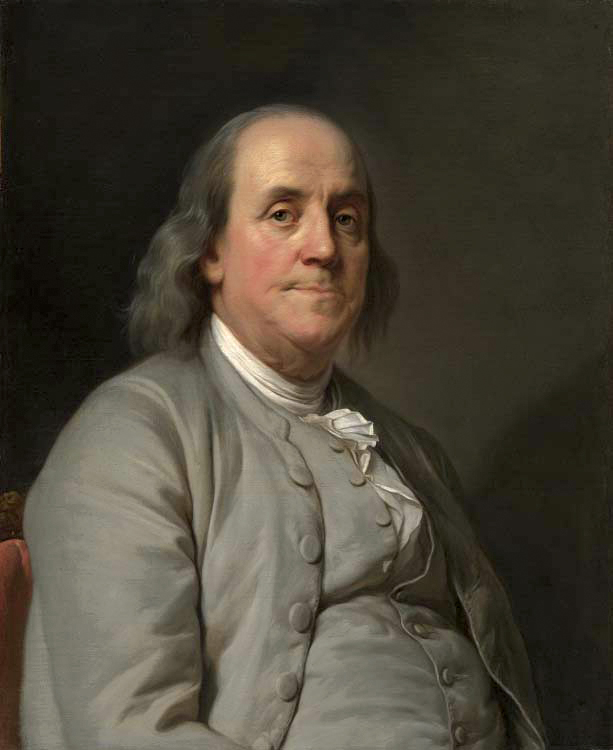

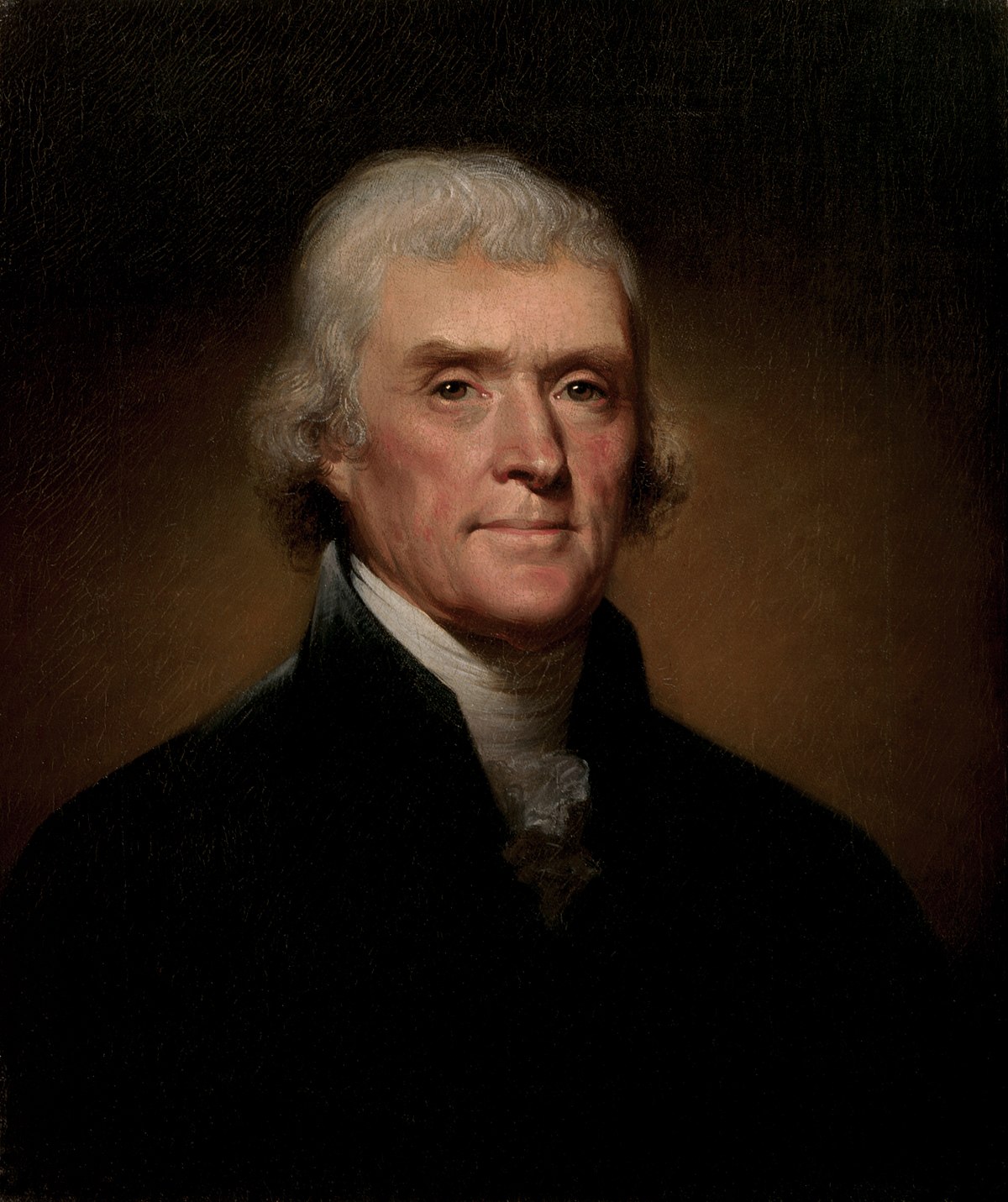

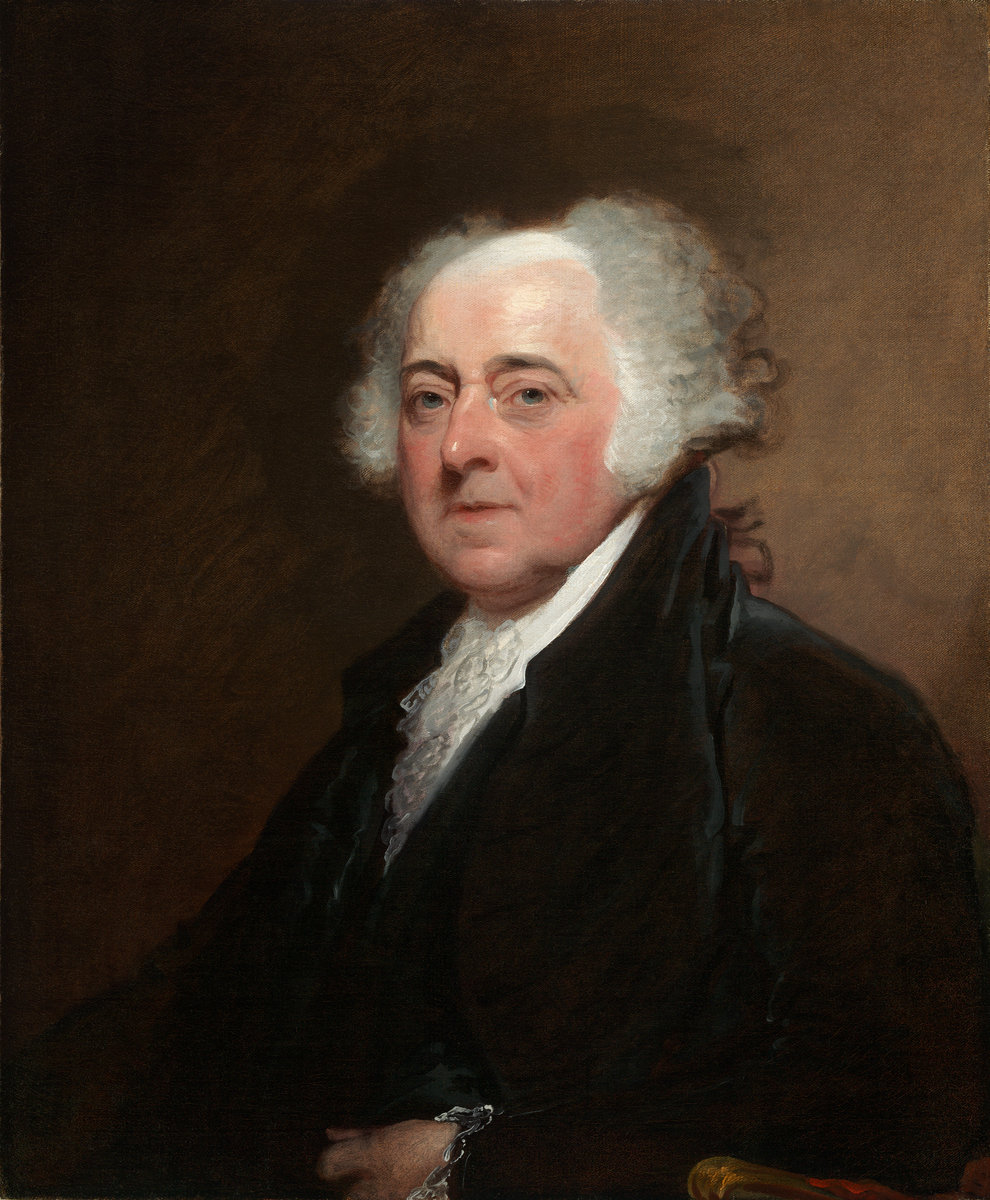

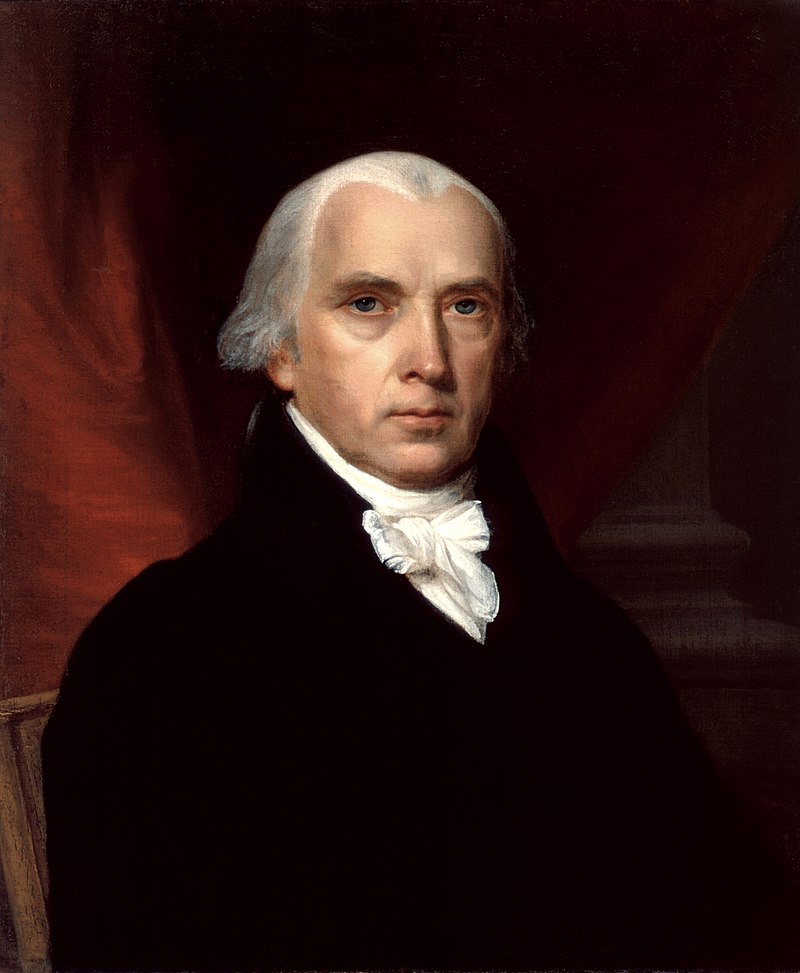

The epithet 'Founding Fathers' often refers to seven individuals, namely Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and James Madison.

In his autobiography, which has issued powerful

self-representations of the homo americanus and has become a highly

canonical text, Franklin fashioned himself as the "good parent"

who "treats all Americans as his offspring". Due to his participation in the campaign for colonial

unity, he was often referred to as "the first American". He is commemorated on the one

hundred-dollar bill.

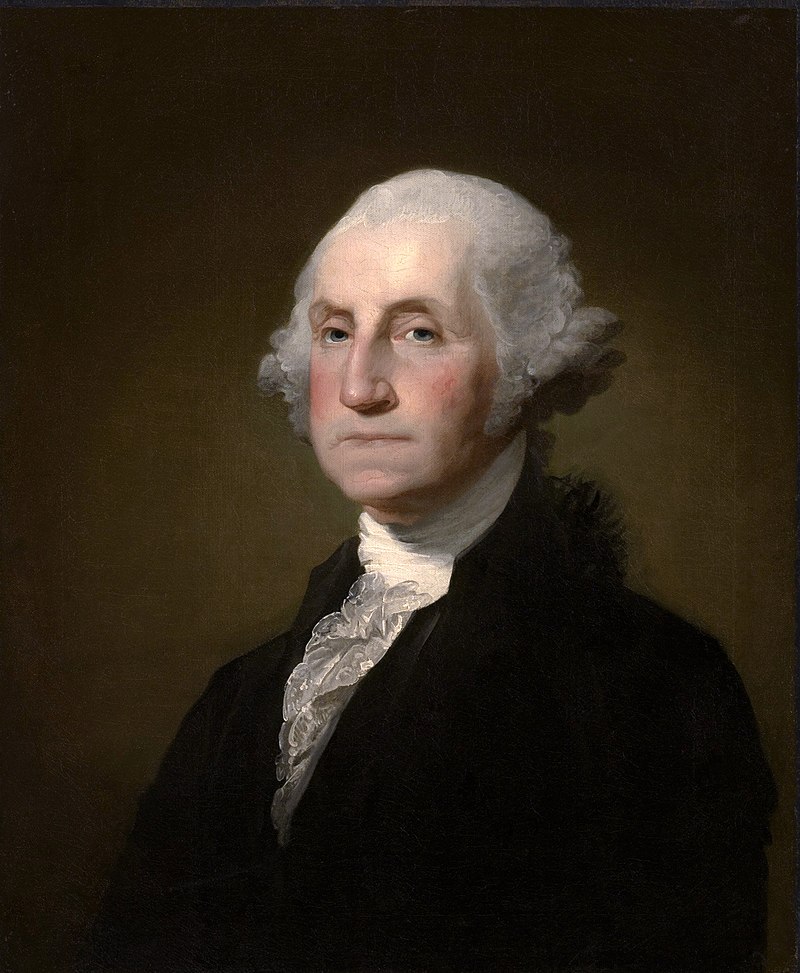

Somewhat different are the grounds on which

George Washington (1732 -1799), one of the three Virginians in this

group, has been elevated as a Founding Father. Washington was

commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775-1783 (and as

such successful against the British military); he then oversaw the

writing of the Constitution in 1787, and was later unanimously voted

the first President of the United States (1789-1797). During his

presidency many aspects and rituals of the US government were

established that are still being practiced today, among them the

presidential inaugural address. Washington has often been given the

epithet 'Father of his Country' and thus holds a particularly

prominent place among the founders. As a Virginian,

Washington was also "a staunch advocate of American expansion" and was among those Founding Fathers who owned

slaves.

Like Washington, Thomas Jefferson

(1743-1826) was a member of the Virginia planter elite and thus a

slaveholder; he served as delegate from Virginia to the Continental

Congress and later on became the third President of the United States

(1801-1809). He

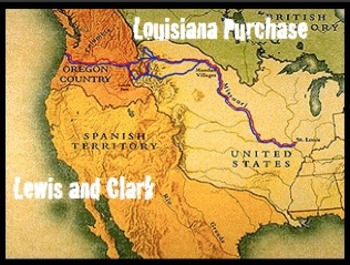

purchased the Louisiana territory from Napoleon in 1803, thus

doubling the size of the US territory, and supported the Lewis and

Clarke expedition (1804-06) to explore it.

The ideal of Jeffersonian democracy is often described as an agrarian vision of an imagined "empire of liberty'.

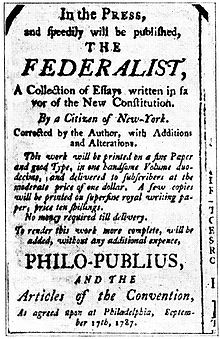

James Madison (1751-1836) is the third

Virginian plantation owner in the ranks of the Founding Fathers. As a

member of Congress, he urged the revision of the Articles of

Confederation in favor of a stronger national government. As the

primary author of the Constitution, he is often called 'Father of

the Constitution' and 'Father of the Bill of Rights.' In

co-authorship with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay he wrote the

Federalist Papers. Power must be divided, Madison argued, both

between federal and state governments, and within the federal

government (checks and balances) to protect individual rights from

what he famously called "the tyranny of the majority".

With Jefferson, Madison formed the Republican Party.

Adams was a lawyer, a political theorist, and the author of "Thoughts on Government," which early on promoted "a checked, balanced, and separated form of government" and suggested a bicameral legislature anchored in the Constitution. As delegate for Massachusetts to the Continental Congress he nominated George Washington as commander-in-chief and supposedly prompted Thomas Jefferson to write the Declaration of Independence. He served as Washington's vice president and later became the second President of the United States

Like Franklin and Adams, John Jay (1745-1829) was from the North and the delegate to the First Continental Congress from New York; he also drafted New York's first state constitution. At first, Jay was, in John Stahr's view, somewhat of a "reluctant democrat" and apparently always favored a strong national government. As head of the Federalist Party, Jay became Governor of the State of New York (1795-1801), and in this function effected the abolition of slavery in this state.

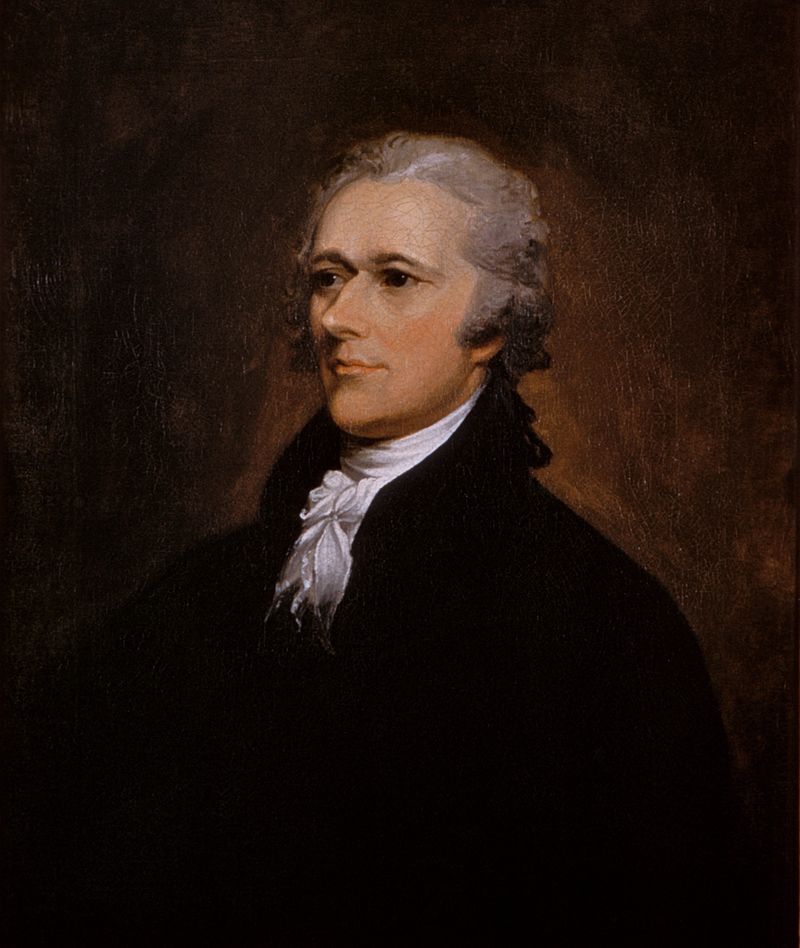

Born and raised in the West Indies, Alexander Hamilton (1755/57(?)-1804) came to North America for his education. Hamilton wrote most of the Federalist Papers and is often considered a nationalist who emphasized a strong central government.

When discussing the iconography of the Founding Fathers, one has to turn once again to the United States Capitol in Washington D.C. and to the rotunda, where crucial scenes from US foundational mythology are exhibited.

The painting entitled The Declaration of Independence is one of the most canonical renderings of the foundational moment of the 'exceptional union' called the United States; its title does not reference the founders' names but their performative act of declaring independence as well as the document confirming that act. It is one among several iconic renderings of foundational moments in US history displayed in the rotunda today.

One of the defining acts of the

Founding Fathers certainly is the signing of the Declaration of

Independence. In the historical context, this doubt

was significant. To gain acceptance for the founding documents among

the states and their delegates it was necessary "to persuade Americans to accept

representation on a scale hitherto unknown" -

namely on a national rather than on a local or regional level. To

achieve this goal, the Founding Fathers created a "new fiction" - i.e., an "American people capable of empowering an

American national government". It seemed uncertain for quite

some time whether Americans would accept this new fiction arguing for

a national union of the individual colonies as a matter of survival.

How can a small group of individuals speak for "the people"? How

could the delegates claim to be "at the point of origin?" Numerous pamphlets as well as the

Federalist Papers were written to produce the much needed consent among the

'American' people and to encourage them to consider themselves as

such: American.

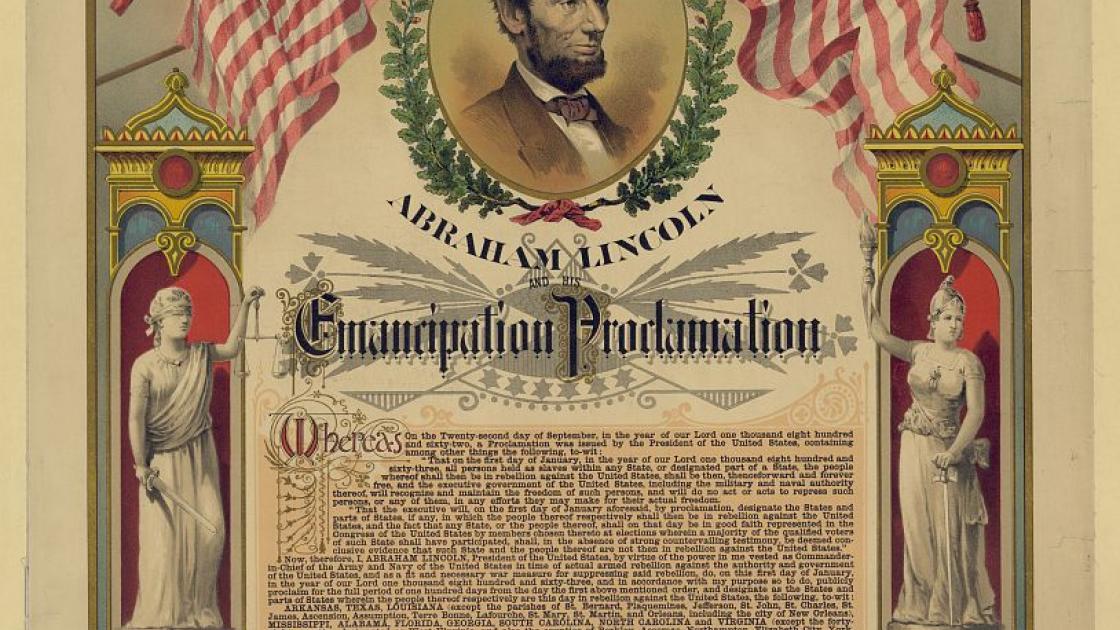

The

continued existence of real slavery in the young republic has to be

seen as one of the most glaring contradictions at the heart of the

new political system created by the Founding Fathers. Despite the

anti-slavery imperative of the Declaration of Independence, the

founding documents not only do not abolish slavery, but the

Constitution ultimately affirms it by way of the Fugitive Slave

Clause and further regulations concerning the representation of the

slave states in the federal government (such as the Three-Fifths

Compromise). Slavery has repeatedly been referred to

as the unfinished business of the American Revolution by which a

system of bondage was

It has also to be noted that the Northern states, one after the other, legislated for the gradual emancipation of slaves. Northern abolition came into increasingly stark contrast with Southern slaveholding and plantation life. By 1810, 75% of all blacks in the North were free, and in 1840 virtually all of them had been emancipated. Of course, abolition in the North did not imply racial equality, quite the contrary - free black people were subjected to racism in all matters of daily private and public life. The paradoxes, contradictions, and (negative) dialectics in the Founding Fathers' political vision revealed by slavery and racial inequality did not remain uncommented on by those who suffered from exclusion on the basis of race.

In many ways, the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, has been viewed as the founding document for African Americans. The Proclamation along with the defeat of the Confederacy and the end of the Civil War is often called a "second founding" or a "re-founding" with regard to the preservation of the national union, the abolition of slavery, and the granting of citizenship to blacks, whereby nearly four million people were freed from lifelong bondage

Much of the discourse on these efforts at reform still crystallizes in the figure of Abraham Lincoln as a symbol of integration, even if the historical accuracy of this assessment is debatable. Lincoln has been referred to as the founding father for African Americans, particularly in the context of civil rights in the 20th century

Barack Obama has invoked Lincoln's presidency and his legacy for African American political culture both as presidential candidate and as elected president. Like Martin Luther King and Jesse Jackson before him, Obama takes up Lincoln's place in a collective black imagination and affirms the great role of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution passed during and after the Civil War. Obama's 2008 speech "A More Perfect Union" has been compared to Lincoln's Cooper Union Speech of 1860 and his Gettysburg Address of 1863.

In the historical context of the Revolution, women were mostly excluded from the political realm

The five justifications for the exclusion of women from political life rooted in stereotypes of women in the late 18th century are reminiscent of the cult of True Womanhood that would dominate much of the 19th century: women's domesticity, women's dependency, women's passions, women's disorders, and women's consent to patriarchy. And yet, the new republic also created a new ideology of gender roles and gender relations. The discourse of Republican Motherhood has been particularly useful to grasp the contradictions of a doctrine that both consolidates and expands women's domestic realm

Linda Kerber and Mary Beth Norton have pointed out how, in the name of the republic, women were esteemed as mothers of future citizens, and how their education, as teachers of the next generation, became more relevant and more acceptable. New educational opportunities opened up, and formal schooling for women improved immensely. As Republican Mothers, women were to raise the citizens and leaders of the republic while remaining firmly confined to the domestic sphere without any direct political participation in a kind of domestic patriotism. In fact, by granting women these educational opportunities, one could claim "that women needed no further political involvement, since they already possessed the power to mold their husbands' and sons' virtuous citizenship". In historical and feminist scholarship, the Republican Mother has alternately been considered a figure of empowerment or of confinement, and clearly remains an ambivalent role model.

One of the most extraordinary examples concerning these ongoing discussions is the controversial Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota. While South Dakota's state historian Doane Robinson originally planned to boost state tourism by having figures from local history carved into the Black Hills, sculptor Gutzon Borglum gave the project a national rather than regional focus and turned it into "a colossal undertaking commemorating the idea of union". Construction began in the 1920s and was concluded in 1941 by Borglum's son, aptly named Lincoln. The sculpture consists of the faces of four presidents carved into Mount Rushmore: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, who signify the "founding, growing, preservation, and development" of the United States of America; Washington clearly symbolizes the nation's founding, Jefferson its expansion (via the Louisiana Purchase), Lincoln the 'preservation' of the Union, and Roosevelt, again, expansion of American hegemony. Thus, each in his own way contributed to the existence and expansion of the US as empire. Alfred Runte sees US national parks as compensating for the absence of castles, ancient ruins, and cathedrals in the US, and Mount Rushmore seems to be a particularly grand example of this kind of compensation.Perhaps not surprisingly, for the entire duration of the construction (1927-41) and even after its completion, the monument has been a matter of contention. The logic of empire resides in its scope as much as in its location, as it is built on land belonging to and considered holy by the Lakota:

It seems difficult to imagine now [...] that there was not substantial negative reaction to the memorial's theme [...]. It is especially astonishing when we take into consideration the irony of location. Here was a planned monument honouring "continental expansion," sited in a territory that, by treaty, still belonged to the Lakota, and that the local Native people considered consecrated ground. Throughout its construction and again with urgency since the 1970s, Native Americans have challenged the rightfulness, validity, and legitimacy of the memorial.

Clearly, the revolutionary events were

not beneficial for the indigenous population, as its claims and

pressures were contained and repelled after the founding even as it

had been involved in the process: it is still little known today (and

the object of controversy) that representatives of the so-called Five

Civilized Tribes were asked to attend the constitutional meetings and

that the Iroquois longhouse served as a model for the framing of the

US Constitution. In this light,

the Mount Rushmore National Memorial may appear as a celebration of

the (white) American triumph over the native population of North America.

As controversial as the Mount Rushmore National Memorial is the initiative of eight chiefs of the Lakota tribe to counter the monument by a Crazy Horse Memorial to display Native heroism in similar fashion to Borglum's project. The work on this counter-monument, which is to even exceed the Mount Rushmore monument in size and scope, began in 1948 and is ongoing. This project has been criticized by Native representatives as imitating the megalomania of white memorial culture and as giving a distorted sense of 'Indianness.'

Another controversy surrounding Mount

Rushmore concerns the question of its patriarchal bias. Rose Arnold

Powell for example campaigned for the inclusion of women's rights

activist Susan B. Anthony on Mount Rushmore:

"I protest with all my being against the exclusion of a woman from the Mount Rushmore group of Great Americans. [...] Future generations will ask why she was left out of the memorial [...] if this blunder is not rectified" . Even though Powell spent much of her life lobbying for Anthony's inclusion in the sculpture and was able to enlist considerable public support for her cause, she was put off time and again by Borglum and others (Borglum's compromise proposal to have Anthony's head carved into the back of the mountain, of course, was unsatisfactory). The inclusion of Anthony as a Founding Mother would certainly have given the monument a decidedly different twist -

Still, we can observe that elite and

popular discourses converge in an unprecedented way in the phenomenon

of founders chic.

Founders chic is often said to begin in

2001 with David McCullough's bestselling biography of John Adams

and the HBO series based on it. The term itself was coined by a

Newsweek journalist, Evan Thomas, in an article titled "Founders

Chic: Live from Philadelphia" (July 9, 2001), and was subsequently

picked up by scholars. It has been described as

"an excessive fascination with the thoughts and actions of a small group of elite men at the expense of other political actors and social groups"

Apart from new individual and collective biographies of the Founding Fathers, we encounter a whole range of founders-chic products on the postmillennial literary market that often lack historical veracity and clearly are predominantly fictional: these include historical novels as well as books dealing with the private lives, families, love interests, and even the hobbies of the Founding Fathers. When we survey the phenomenon of founders chic, we cannot but concede that the Founding Fathers have become a best-selling bran.

Beneath all the human interest, these products revitalize the notion of individual heroism that had already largely been dismissed in critical work on the founders. Reiterating the purposefulness and telos of the founding and reinstating the Founding Fathers as authority figures and role models at the beginning of the 21st century may be considered as an indication of some sort of crisis; founders chic, then, on one level, registers and is symptomatic of that crisis, whereas, on another level, it is an attempt to overcome that crisis. Most of the manifestations of the founders chic phenomenon are utterly nostalgic; they pretend to return us to "an earlier era of genuine statesmen" in both private and political life. Thus, they have been read as reinforcing moral standards (for instance, McCullough's comparison of John and Abigail Adams's marital union with Bill Clinton's "extramarital exploits" (Nobles, "Historians" 139). In another commentary we find references to a "post 9/11 crisis" that would endear Americans to the founders once again

What is striking about this "fantasy

nation" envisioned in The Founding Foodies and similar founders

chic publications in which the Founding Fathers once more reign

supreme, is that

(1) it re-inscribes social hierarchies;

(2) it

reerects and legitimates discursive systems of oppression and

exclusion (it definitely flirts with past injustices such as slavery,

etc.);

(3) it re-establishes a European genealogy of American

national culture by way of French cuisine (obviously the black slave

would not be able to cook if he had not been trained to do so in France);

(4) it romanticizes consumption and obscures the conditions of production, i.e. slave labor - after all, it is slaves who put into practice all of the glorious ideas about composting, fermenting, wine-growing etc.;

(5)

it (re)sacralizes the Founding Fathers by giving them celebrity

status - visiting Monticello or Mount Vernon in person or through

the consumption of founders chic products may qualify as a kind of

civil religious 'pilgrimage' as much as visiting Washington,

D.C.; Founders chic thus clearly is part of a

broader marketing of nostalgic images of a "normal," "familial"

America.

This is also reflected in the way that the Founding Fathers mythology is used for instance by the activists and advocates of the Tea Party movement.

The Liberty Tower at Ground Zero

symbolizes a national fantasy that refers, by way of its height of

1,776 feet, to the year of the Declaration of Independence. This new

architectural symbol also reinforces and re-invigorates the myth of

the founding and the Founding Fathers. Particularly in the wake of

9/11, we can observe a political climate in which many Americans were

protective of the Founding Fathers again.

Thus, we may relate the comeback of the founders in founders chic to other political developments and movements which affirm their role for the national founding, the new historical revisionism initiated by the Tea Party movement and religious groups alike presents a confused discursive conglomerate that is "conflating originalism, evangelicalism, and heritage tourism" and which "amounts to fundamentalism.

In this fundamentalist discourse, the

Founding Fathers serve as the historical authority for

neoconservative and evangelical agendas; this imagined alliance

highlights the activists' lack of historical knowledge or their

willingness to purposefully misrepresent history to further their own

ends.

It is well-known that, in an interview with Glenn Beck on January 13, 2010, former Governor of Alaska Sarah Palin (R) invoked the "sincerity of the Founding Fathers" and yet was at first unable to name even one of them. Similarly, Congresswoman Michele Bachmann (R-Min) falsely claimed that "the very founders that wrote those [founding] documents worked tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States [...]," and went on to say that John Quincy Adams "would not rest until slavery was extinguished in the country. This skewed and counterfactual version of history shows that the Founding Fathers are used here as a projection screen for the present which enables a fantasy of the nation through a retrospectively imagined original, primary moment.

The Tea Party movement has been considered by many commentators and scholars to advocate an extremist political agenda based on anti-elitism and antistatism, even as it lacks a consistent common ideology

The so-called "teavangelicals" as David Brody calls them appreciatively (cf. his book of the same title), even as they present two distinct groups (i.e., Tea Party movement activists and evangelical Christians), can be considered aligned on a variety of issues. For one thing, both converge in a new embrace of the myth of the Founding Fathers under political and religious considerations, respectively, and share a unilateral, patriotic discourse that identifies outside, 'foreign' influences and US international involvement as harmful to the US. These anxieties come to the fore in discussions of Obama's birth certificate (revolving around the question of whether he is a foreigner, i.e. 'un-American'), in blaming foreign (European) influence for the secularization of the US, as well as in post-9/11 discussions of the 'terrorist threat.' The discussion of the Founding Fathers continues to be deeply polarized, and the founders' original intent is time and again debated in political arguments that are still often quite divisive.