K2M Tronc commun

1

Nature

The Vocabulary Guide : chapter 80

literary terms : REMIND

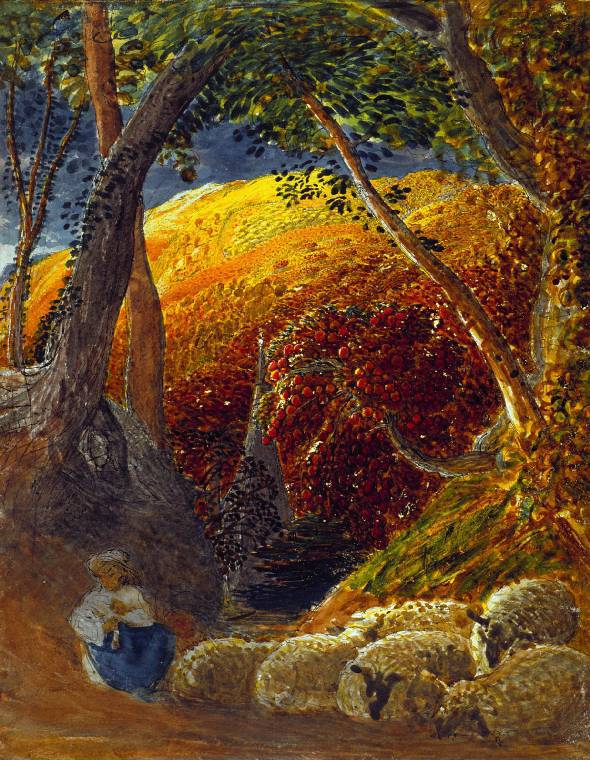

The Magic Apple Tree, 1830, Samuel Palmer

The Great Day of His Wrath,1853, John Martin

Emily Brontee Wuthering Heights, 1847

Yesterday afternoon set in misty and cold. I had half a mind to spend it by my study fire, instead of wading through heath and mud to Wuthering Heights. On coming up from dinner, however, (N.B.-I dine between twelve and one o'clock; the housekeeper, a matronly lady, taken as a fixture along with the house, could not, or would not, comprehend my request that I might be served at five)-on mounting the stairs with this lazy intention, and stepping into the room, I saw a servant-girl on her knees surrounded by brushes and coal-scuttles, and raising an infernal dust as she extinguished the flames with heaps of cinders. This spectacle drove me back immediately; I took my hat, and, after a four-miles' walk, arrived at Heathcliff's garden-gate just in time to escape the first feathery flakes of a snow-shower.

On that bleak hill-top the earth was hard with a black frost, and the air made me shiver through every limb. Being unable to remove the chain, I jumped over, and, running up the flagged causeway bordered with straggling gooseberry-bushes, knocked vainly for admittance, till my knuckles tingled and the dogs howled.

'Wretched inmates!' I ejaculated, mentally, 'you deserve perpetual isolation from your species for your churlish inhospitality. At least, I would not keep my doors barred in the day-time. I don't care-I will get in!' So resolved, I grasped the latch and shook it vehemently. Vinegar-faced Joseph projected his head from a round window of the barn.

'What are ye for?' he shouted. 'T' maister's down i' t' fowld. Go round by th' end o' t' laith, if ye went to spake to him.'

'Is there nobody inside to open the door?' I hallooed, responsively.

'There's nobbut t' missis; and shoo'll not oppen 't an ye mak' yer flaysome dins till neeght.'

'Why? Cannot you tell her whom I am, eh, Joseph?'

'Nor-ne me! I'll hae no hend wi't,' muttered the head, vanishing.

The snow began to drive thickly. I seized the handle to essay another trial; when a young man without coat, and shouldering a pitchfork, appeared in the yard behind. He hailed me to follow him, and, after marching through a wash-house, and a paved area containing a coal-shed, pump, and pigeon-cot, we at length arrived in the huge, warm, cheerful apartment where I was formerly received. It glowed delightfully in the radiance of an immense fire, compounded of coal, peat, and wood; and near the table, laid for a plentiful evening meal, I was pleased to observe the 'missis,' an individual whose existence I had never previously suspected. I bowed and waited, thinking she would bid me take a seat. She looked at me, leaning back in her chair, and remained motionless and mute.

'Rough weather!' I remarked. 'I'm afraid, Mrs. Heathcliff, the door must bear the consequence of your servants' leisure attendance: I had hard work to make them hear me.'

She never opened her mouth. I stared-she stared also: at any rate, she kept her eyes on me in a cool, regardless manner, exceedingly embarrassing and disagreeable.

'Sit down,' said the young man, gruffly. 'He'll be in soon.'

I obeyed; and hemmed, and called the villain Juno, who deigned, at this second interview, to move the extreme tip of her tail, in token of owning my acquaintance.

'A beautiful animal!' I commenced again. 'Do you intend parting with the little ones, madam?'

'They are not mine,' said the amiable hostess, more repellingly than Heathcliff himself could have replied.

'Ah, your favourites are among these?' I continued, turning to an obscure cushion full of something like cats.

'A strange choice of favourites!' she observed scornfully.

Unluckily, it was a heap of dead rabbits. I hemmed once more, and drew closer to the hearth, repeating my comment on the wildness of the evening.

'You should not have come out,' she said, rising and reaching from the chimney-piece two of the painted canisters.

Her position before was sheltered from the light; now, I had a distinct view of her whole figure and countenance. She was slender, and apparently scarcely past girlhood: an admirable form, and the most exquisite little face that I have ever had the pleasure of beholding; small features, very fair; flaxen ringlets, or rather golden, hanging loose on her delicate neck; and eyes, had they been agreeable in expression, that would have been irresistible: fortunately for my susceptible heart, the only sentiment they evinced hovered between scorn and a kind of desperation, singularly unnatural to be detected there. The canisters were almost out of her reach; I made a motion to aid her; she turned upon me as a miser might turn if any one attempted to assist him in counting his gold.

'I don't want your help,' she snapped; 'I can get them for myself.'

'I beg your pardon!' I hastened to reply.

'Were you asked to tea?' she demanded, tying an apron over her neat black frock, and standing with a spoonful of the leaf poised over the pot.

'I shall be glad to have a cup,' I answered.

'Were you asked?' she repeated.

'No,' I said, half smiling. 'You are the proper person to ask me.'

She flung the tea back, spoon and all, and resumed her chair in a pet; her forehead corrugated, and her red under-lip pushed out, like a child's ready to cry.

version 1

"Which way now?"Tom said

he had no idea. Julian said they were lost, no one would find them, rats

would pick their bones. Someone sneezed. Julian said"I told you, don't

do that.""I didn't. It must have been him."Tom was worried about hunting

down a probably harmless and innocent boy. He was also worried about

encountering a savage and dangerous boy.Julian cried "We know you're

there. Come out and give yourself up!"He was alert and smiling, Tom saw,

the successful seeker or catcher in games of pursuit.There was a

silence. Another sneeze. A slight scuffling. Julian and Tom

turned to look down the other fork of the corridor, which was

obstructed by a forest of imitation marble pillars, made to support

busts or vases. A wild face, under a mat of hair, appeared at knee

height, framed between fake basalt and fake obsidian."You'd better

come out and explain yourself," said Julian, with complete

certainty. "You're trespassing. I should get the police."The third

boy came out on all fours, shook himself like a beast, and

stood up, supporting himself briefly on the pillars. He was about

Julian's height. He was shaking, whether with fear or wrath Tom could

not tell.

A.S. Byatt, The Children's Book, 2010.

Edgar Poe William Wilson,1839

It was at Rome, during the Carnival of 18--, that I attended a masquerade in the palazzo of the Neapolitan Duke Di Broglio. I had indulged more freely than usual in the excesses of the wine-table; and now the suffocating atmosphere of the crowded rooms irritated me beyond endurance. The difficulty, too, of forcing my way through the mazes of the company contributed not a little to the ruffling of my temper; for I was anxiously seeking, (let me not say with what unworthy motive) the young, the gay, the beautiful wife of the aged and doting Di Broglio. With a too unscrupulous confidence she had previously communicated to me the secret of the costume in which she would be habited, and now, having caught a glimpse of her person, I was hurrying to make my way into her presence. --At this moment I felt a light hand placed upon my shoulder, and that ever-remembered, low, damnable whisper within my ear.

In an absolute phrenzy of wrath, I turned at once upon him who had thus interrupted me, and seized him violently by tile collar. He was attired, as I had expected, in a costume altogether similar to my own; wearing a Spanish cloak of blue velvet, begirt about the waist with a crimson belt sustaining a rapier. A mask of black silk entirely covered his face.

"Scoundrel!" I said, in a voice husky with rage, while every syllable I uttered seemed as new fuel to my fury, "scoundrel! impostor! accursed villain! you shall not --you shall not dog me unto death! Follow me, or I stab you where you stand!" --and I broke my way from the ball-room into a small ante-chamber adjoining --dragging him unresistingly with me as I went.

Upon entering, I thrust him furiously from me. He staggered against the wall, while I closed the door with an oath, and commanded him to draw. He hesitated but for an instant; then, with a slight sigh, drew in silence, and put himself upon his defence.

The contest was brief indeed. I was frantic with every species of wild excitement, and felt within my single arm the energy and power of a multitude. In a few seconds I forced him by sheer strength against the wainscoting, and thus, getting him at mercy, plunged my sword, with brute ferocity, repeatedly through and through his bosom.

At that instant some person tried the latch of the door. I hastened to prevent an intrusion, and then immediately returned to my dying antagonist. But what human language can adequately portray that astonishment, that horror which possessed me at the spectacle then presented to view? The brief moment in which I averted my eyes had been sufficient to produce, apparently, a material change in the arrangements at the upper or farther end of the room. A large mirror, --so at first it seemed to me in my confusion --now stood where none had been perceptible before; and, as I stepped up to it in extremity of terror, mine own image, but with features all pale and dabbled in blood, advanced to meet me with a feeble and tottering gait.

Thus it appeared, I say, but was not. It was my antagonist --it was Wilson, who then stood before me in the agonies of his dissolution. His mask and cloak lay, where he had thrown them, upon the floor. Not a thread in all his raiment --not a line in all the marked and singular lineaments of his face which was not, even in the most absolute identity, mine own!

It was Wilson; but he spoke no longer in a whisper, and I could have fancied that I myself was speaking while he said:

"You have conquered, and I yield. Yet, henceforward art thou also dead --dead to the World, to Heaven and to Hope! In me didst thou exist --and, in my death, see by this image, which is thine own, how utterly thou hast murdered thyself."

Examples and effects of alliterations :

Version 2

The Vocabulary Guide : chapter 68

literary terms : ILLUSTRATE

A Hind's Daughter, 1883, James Guthrie

Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward,1874,Sir Samuel Luke Fildes

Charles Dickens Great Expectations,1861

My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

I give Pirrip as my father's family name, on the authority of his tombstone and my sister,-Mrs. Joe Gargery, who married the blacksmith. As I never saw my father or my mother, and never saw any likeness of either of them (for their days were long before the days of photographs), my first fancies regarding what they were like were unreasonably derived from their tombstones. The shape of the letters on my father's, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, "Also Georgiana Wife of the Above," I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly. To five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine,-who gave up trying to get a living, exceedingly early in that universal struggle,-I am indebted for a belief I religiously entertained that they had all been born on their backs with their hands in their trousers-pockets, and had never taken them out in this state of existence.

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening. At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.

"Hold your noise!" cried a terrible voice, as a man started up from among the graves at the side of the church porch. "Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!"

A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared, and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

"Oh! Don't cut my throat, sir," I pleaded in terror. "Pray don't do it, sir."

"Tell us your name!" said the man. "Quick!"

"Pip, sir."

"Once more," said the man, staring at me. "Give it mouth!"

"Pip. Pip, sir."

"Show us where you live," said the man. "Pint out the place!"

I pointed to where our village lay, on the flat in-shore among the alder-trees and pollards, a mile or more from the church.

The man, after looking at me for a moment, turned me upside down, and emptied my pockets. There was nothing in them but a piece of bread. When the church came to itself,-for he was so sudden and strong that he made it go head over heels before me, and I saw the steeple under my feet,-when the church came to itself, I say, I was seated on a high tombstone, trembling while he ate

Version 3

Miss Lucy was the only guardian present. She was leaning over the rail at the front, peering into the rain like she was trying to see right across the playing field. I was watching her as carefully as ever in those days, and even as I was laughing at Laura, I was stealing glances at Miss Lucy's back. I remember wondering if there wasn't something a bit odd about her posture, the way her head was bent down just a little too far so she looked like a crouching animal waiting to pounce. And the way she was leaning forward over the rail meant drops from the overhanging gutter were only just missing her - but she seemed to show no sign of caring. I remember actually convincing myself there was nothing unusual in all this - that she was simply anxious for the rain to stop - and turning my attention back to what Laura was saying. Then a few minutes later, when I'd forgotten all about Miss Lucy and was laughing my head off at something, I suddenly realised things had gone quiet around us, and that Miss Lucy was speaking. She was standing at the same spot as before, but she'd turned to face us now, so her back was against the rail, and the rainy sky behind her.

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go,2005.

4

Naturalism

The Vocabulary Guide : chapter 13

literary terms : EMPHASIS

The Lady of Shalott,1888, John William Waterhouse

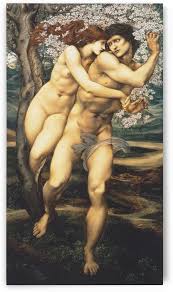

The Tree of Forgiveness, 1887, Edward Burne-Jones

Thomas Hardy Jude The Obscure,1895

he (Sue) joined Jude in a hasty meal, and in a quarter of an hour they started together, resolving to clear out from Sue's too respectable lodging immediately. On reaching the place and going upstairs she found that all was quiet in the children's room, and called to thelandlady in timorous tones to please bring up the tea-kettle and something for their breakfast. This was perfunctorily done, and producing a couple of eggs which she had brought with her she put them into the boiling kettle, and summoned Jude to watch them for the youngsters, while she went to call them, it being now about half-past eight o'clock.

Jude stood bending over the kettle, with his watch in his hand,timing the eggs, so that his back was turned to the little inner chamber where the children lay. A shriek from Sue suddenly caused him to start round. He saw that the door of the room, or rather closet--which had seemed to go heavily upon its hinges as she pushed it back--was open, and that Sue had sunk to the floor just within it. Hastening forward to pick her up he turned his eyes to the little bed spread on the boards; no children were there. He looked in bewilderment round the room. At the back of the door were fixed two hooks for hanging garments, and from these the forms of the two youngest children were suspended, by a piece of box-cord round each of their necks, while from a nail a few yards off the body of little Jude was hanging in a similar manner. An overturned chair was near the elder boy, and his glazed eyes were slanted into the room; but those of the girl and the baby boy were closed.

Half-paralyzed by the

strange and consummate horror of the scene he let Sue lie, cut the

cords with his pocket-knife and threw the three children on the bed;

but the feel of their bodies in the momentary

handling seemed to

say that they were dead. He caught up Sue, who was in fainting fits,

and put her on the bed in the other room, after which he breathlessly

summoned the landlady and ran out for a doctor.

When he got back Sue had come to herself, and the two helpless women, bending over the children in wild efforts to restore them, and the triplet of little corpses, formed a sight which overthrew his self-command. The nearest surgeon came in, but, as Jude had inferred, his presence was superfluous. The children were past saving, for though their bodies were still barely cold it was conjectured that they had been hanging more than an hour. The probability held by the parents later on, when they were able to reason on the case, was that the elder boy, on waking, looked into the outer room for Sue, and, finding her absent, was thrown into a fit of aggravated despondency that the events and information of the evening before had induced in his morbid temperament. Moreover a piece of paper was found upon the floor, on which was written, in the boy's hand, with the bit of lead pencil that he carried:

_Done because we are too menny._

At sight of this Sue's nerves utterly gave way, an awful conviction that her discourse with the boy had been the main cause of the tragedy, throwing her into a convulsive agony which knew no abatement. They carried her away against her wish to a room on the lower floor; and there she lay, her slight figure shaken with her gasps, and her eyes staring at the ceiling, the woman of the house vainly trying to soothe her.

They could hear from

this chamber the people moving about above, and she implored to be

allowed to go back, and was only kept from doing so by the assurance

that, if there were any hope, her presence might do harm, and the

reminder that it was necessary to take care of herself lest she

should endanger a coming life. Her inquiries were incessant, and at

last Jude came down and told her there was no hope.

As soon as she

could speak she informed him what she had said to the boy, and how

she thought herself the cause of this.

"No," said Jude. "It was in his nature to do it. The doctor says there are such boys springing up amongst us--boys of a sort unknown in the last generation--the outcome of new views of life. They seem to see all its terrors before they are old enough to have staying power to resist them. He says it is the beginning of the coming universal wish not to live. He's an advanced man, the doctor: but he can give no consolation to--"

Jude had kept back his own grief on account of her; but he now broke down; and this stimulated Sue to efforts of sympathy which in some degree distracted her from her poignant self-reproach.

Version 4

The Life Line, 1884, Winslow Homer

Eight Bells, 1886, Winslow Homer

Herman Melville Moby Dick, 1851

CHAPTER 1. Loomings.Call me Ishmael. Some years ago-never mind how long precisely-having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off-then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.

There now is your insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral reefs-commerce surrounds it with her surf. Right and left, the streets take you waterward. Its extreme downtown is the battery, where that noble mole is washed by waves, and cooled by breezes, which a few hours previous were out of sight of land. Look at the crowds of water-gazers there.

Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall, northward. What do you see?-Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries. Some leaning against the spiles; some seated upon the pier-heads; some looking over the bulwarks of ships from China; some high aloft in the rigging, as if striving to get a still better seaward peep. But these are all landsmen; of week days pent up in lath and plaster-tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks. How then is this? Are the green fields gone? What do they here?

But look! here come more crowds, pacing straight for the water, and seemingly bound for a dive. Strange! Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land; loitering under the shady lee of yonder warehouses will not suffice. No. They must get just as nigh the water as they possibly can without falling in. And there they stand-miles of them-leagues. Inlanders all, they come from lanes and alleys, streets and avenues-north, east, south, and west. Yet here they all unite. Tell me, does the magnetic virtue of the needles of the compasses of all those ships attract them thither?

Once more. Say you are in the country; in some high land of lakes. Take almost any path you please, and ten to one it carries you down in a dale, and leaves you there by a pool in the stream. There is magic in it. Let the most absent-minded of men be plunged in his deepest reveries-stand that man on his legs, set his feet a-going, and he will infallibly lead you to water, if water there be in all that region. Should you ever be athirst in the great American desert, try this experiment, if your caravan happen to be supplied with a metaphysical professor. Yes, as every one knows, meditation and water are wedded for ever.

But here is an artist. He desires to paint you the dreamiest, shadiest, quietest, most enchanting bit of romantic landscape in all the valley of the Saco

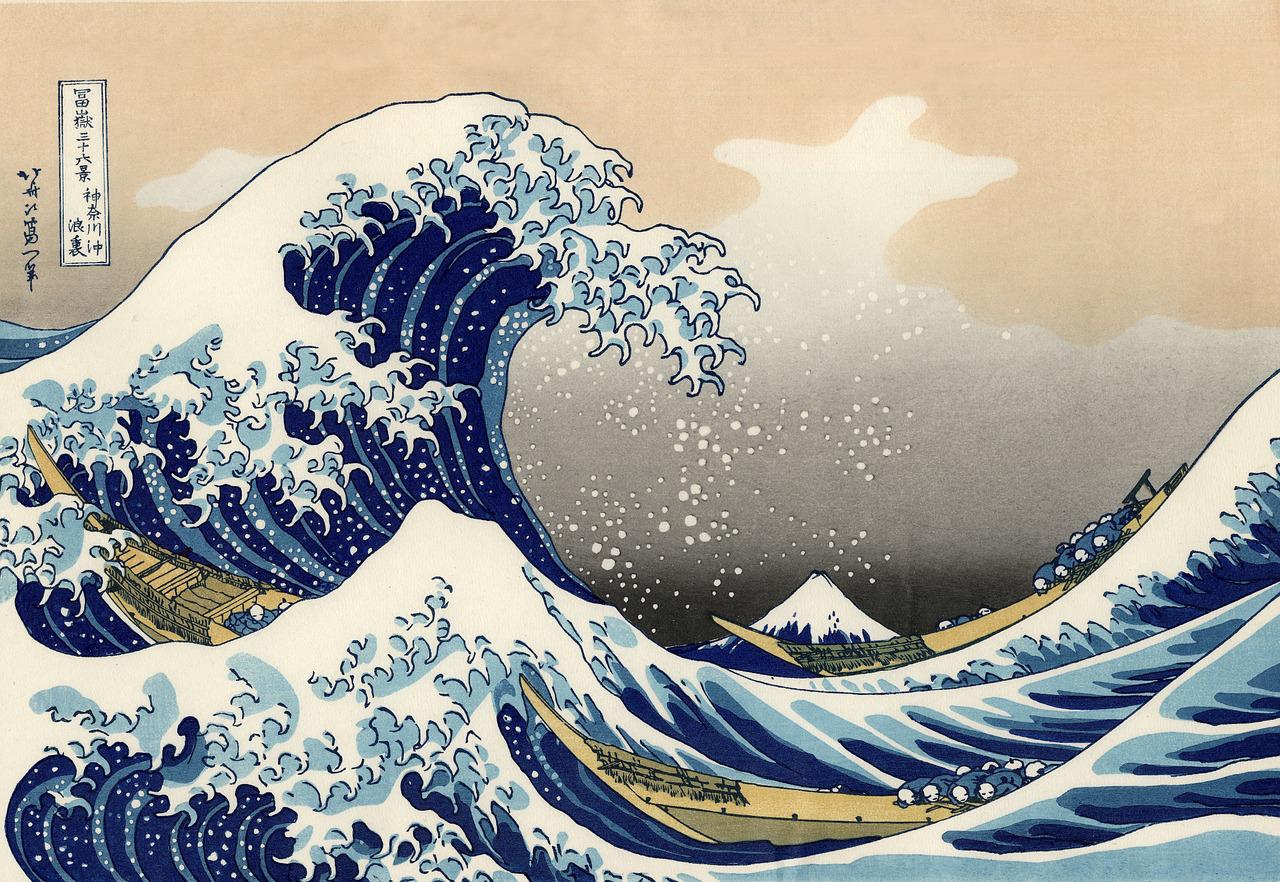

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Kokusai, 1831

Version 5

There is one window high up -you cannot see out of it. My bed had doors but they have been taken away. There is not much else in the room. Her bed, a black press, the table in the middle and two black chairs carved with fruit and flowers. They have high backs and no arms. The dressing-room is very small, the room next to this one is hung with tapestry. Looking at the tapestry one day I recognized my mother dressed in an evening gown but with bare feet. She looked away from me, over my head just as she used to do. I wouldn't tell Grace this. Her name oughtn't to be Grace. Names matter, like when he wouldn't call me Antoinette, and I saw Antoinette drifting out of the window with her scents, her pretty clothes and her looking-glass.There is no looking-glass here and I don't know what I am like now. I remember watching myself brush my hair and how my eyes looked back at me. The girl I saw was myself yet not quite myself. Long ago when I was a child and very lonely I tried to kiss her. But the glass was between us -hard, cold and misted over with my breath.

Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966.

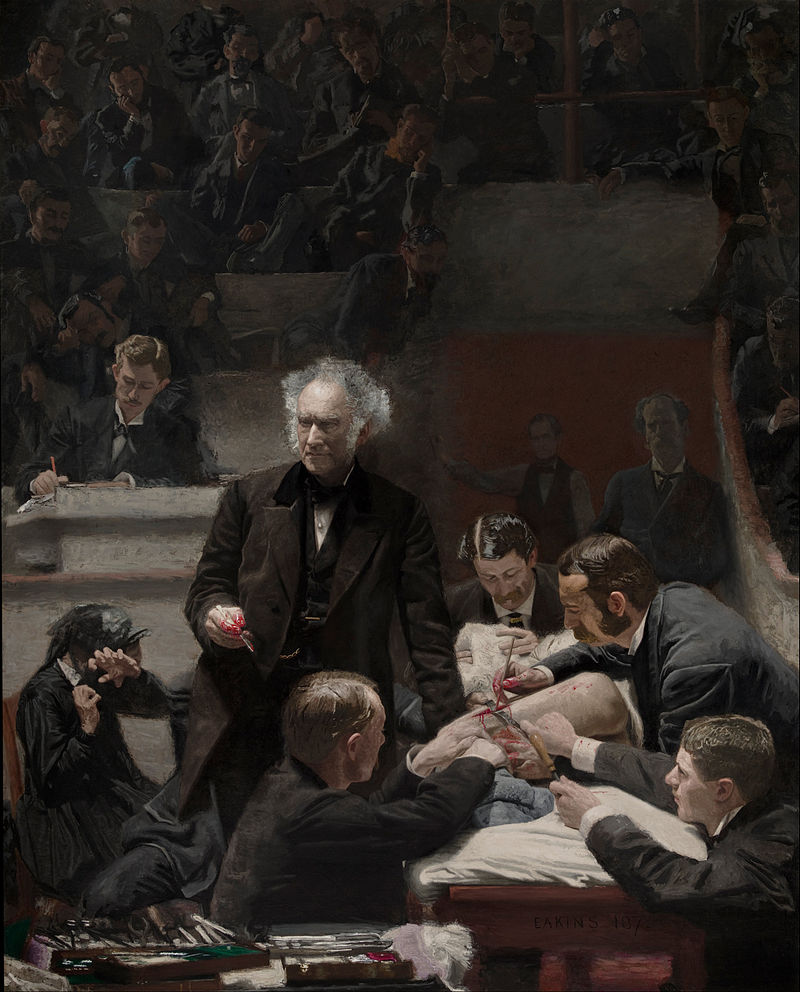

The Gross Clinic,1875, Thomas Eakins

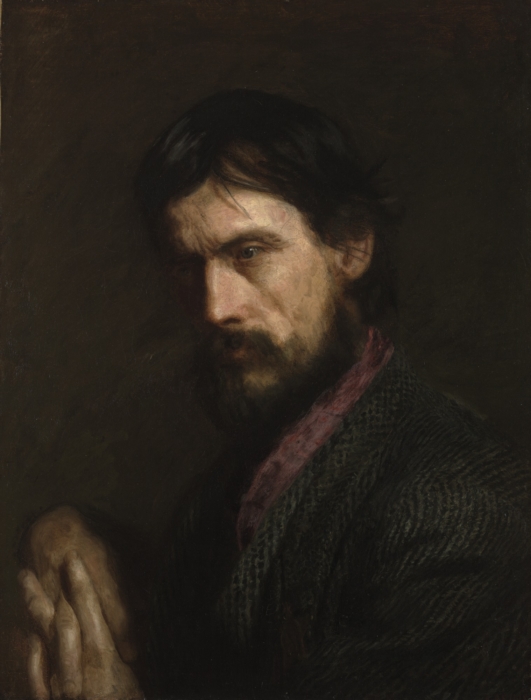

The Veteran portrait of George Reynolds,1885, Thomas Eakins

Mark Twain Life on the Mississippi,1883

WHEN I was a boy, there was but one permanent ambition among my comrades in our village on the west bank of the Mississippi River. That was, to be a steamboatman. We had transient ambitions of other sorts, but they were only transient. When a circus came and went, it left us all burning to become clowns; the first negro minstrel show that came to our section left us all suffering to try that kind of life; now and then we had a hope that if we lived and were good, God would permit us to be pirates. These ambitions faded out, each in its turn; but the ambition to be a steamboatman always remained.

Once a day a cheap, gaudy packet arrived upward from St. Louis, and another downward from Keokuk. Before these events, the day was glorious with expectancy; after them, the day was a dead and empty thing. Not only the boys, but the whole village, felt this. After all these years I can picture that old time to myself now, just as it was then: the white town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer's morning; the streets empty, or pretty nearly so; one or two clerks sitting in front of the Water Street stores, with their splint-bottomed chairs tilted back against the wall, chins on breasts, hats slouched over their faces, asleep-with shingle-shavings enough around to show what broke them down; a sow and a litter of pigs loafing along the sidewalk, doing a good business in watermelon rinds and seeds; two or three lonely little freight piles scattered about the 'levee;' a pile of 'skids' on the slope of the stone-paved wharf, and the fragrant town drunkard asleep in the shadow of them; two or three wood flats at the head of the wharf, but nobody to listen to the peaceful lapping of the wavelets against them; the great Mississippi, the majestic, the magnificent Mississippi, rolling its mile-wide tide along, shining in the sun; the dense forest away on the other side; the 'point' above the town, and the 'point' below, bounding the river-glimpse and turning it into a sort of sea, and withal a very still and brilliant and lonely one. Presently a film of dark smoke appears above one of those remote 'points;' instantly a negro drayman, famous for his quick eye and prodigious voice, lifts up the cry, 'S-t-e-a-m-boat a-comin'!' and the scene changes! The town drunkard stirs, the clerks wake up, a furious clatter of drays follows, every house and store pours out a human contribution, and all in a twinkling the dead town is alive and moving.

Drays, carts, men, boys, all go hurrying from many quarters to a common center, the wharf. Assembled there, the people fasten their eyes upon the coming boat as upon a wonder they are seeing for the first time. And the boat is rather a handsome sight, too. She is long and sharp and trim and pretty; she has two tall, fancy-topped chimneys, with a gilded device of some kind swung between them; a fanciful pilot-house, a glass and 'gingerbread', perched on top of the 'texas' deck behind them; the paddle-boxes are gorgeous with a picture or with gilded rays above the boat's name; the boiler deck, the hurricane deck, and the texas deck are fenced and ornamented with clean white railings; there is a flag gallantly flying from the jack-staff; the furnace doors are open and the fires glaring bravely; the upper decks are black with passengers; the captain stands by the big bell, calm, imposing, the envy of all; great volumes of the blackest smoke are rolling and tumbling out of the chimneys-a husbanded grandeur created with a bit of pitch pine just before arriving at a town; the crew are grouped on the forecastle; the broad stage is run far out over the port bow, and an envied deckhand stands picturesquely on the end of it with a coil of rope in his hand; the pent steam is screaming through the gauge-cocks, the captain lifts his hand, a bell rings, the wheels stop; then they turn back, churning the water to foam, and the steamer is at rest. Then such a scramble as there is to get aboard, and to get ashore, and to take in freight and to discharge freight, all at one and the same time; and such a yelling and cursing as the mates facilitate it all with! Ten minutes later the steamer is under way again, with no flag on the jack-staff and no black smoke issuing from the chimneys. After ten more minutes the town is dead again, and the town drunkard asleep by the skids once more.

Version 6

As the beginning of term approached, the Departmental corridor lost its tomb-like silence, its air of human desertion. The faculty began to trickle back to their posts. From behind his desk he heard them passing in the corridor, greeting each other, laughing and opening and shutting their doors. But when he ventured into the corridor himself they seemed to avoid him, bolting into their offices just as he emerged from his own, or else they looked straight through him as if he were the man who serviced the central heating. Just when he had decided that he would have to take the initiative by ambushing his British colleagues as they passed his door at coffee-time and dragging them into his office, they began to acknowledge his presence in a way which suggested long but not deep familiarity, tossing him a perfunctory smile as they passed, or nodding their heads, without breaking step or their own conversations. This new behaviour implied that they all knew perfectly well who he was, thus making any attempt at self-introduction on his part superfluous, while at the same time it offered no purchase for extending acquaintance.

David Lodge,Changing Places, 1975.

7

Perception

The Vocabulary Guide : chapter 9

literary terms : intertextuality and echoes

Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge,1879, Mary Cassatt

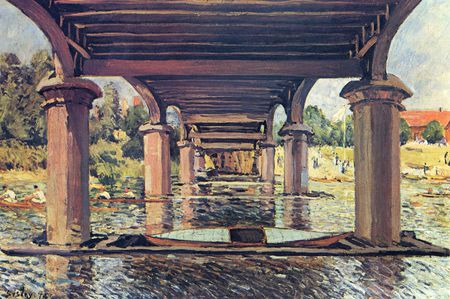

Under Hampton Court Bridge,1874, Alfred Sisley

Henry James The American,1876

As the little copyist proceeded with her work, she sent every now and then a responsive glance toward her admirer. The cultivation of the fine arts appeared to necessitate, to her mind, a great deal of by-play, a great standing off with folded arms and head drooping from side to side, stroking of a dimpled chin with a dimpled hand, sighing and frowning and patting of the foot, fumbling in disordered tresses for wandering hair-pins. These performances were accompanied by a restless glance, which lingered longer than elsewhere upon the gentleman we have described. At last he rose abruptly, put on his hat, and approached the young lady. He placed himself before her picture and looked at it for some moments, during which she pretended to be quite unconscious of his inspection. Then, addressing her with the single word which constituted the strength of his French vocabulary, and holding up one finger in a manner which appeared to him to illuminate his meaning, "Combien?" he abruptly demanded.

The artist stared a moment, gave a little pout, shrugged her shoulders, put down her palette and brushes, and stood rubbing her hands.

"How much?" said our friend, in English. "Combien?"

"Monsieur wishes to buy it?" asked the young lady in French.

"Very pretty, splendide. Combien?" repeated the American.

"It pleases monsieur, my little picture? It's a very beautiful subject," said the young lady.

"The Madonna, yes; I am not a Catholic, but I want to buy it. Combien? Write it here." And he took a pencil from his pocket and showed her the fly-leaf of his guide-book. She stood looking at him and scratching her chin with the pencil. "Is it not for sale?" he asked. And as she still stood reflecting, and looking at him with an eye which, in spite of her desire to treat this avidity of patronage as a very old story, betrayed an almost touching incredulity, he was afraid he had offended her. She was simply trying to look indifferent, and wondering how far she might go. "I haven't made a mistake-pas insulté, no?" her interlocutor continued. "Don't you understand a little English?"

The young lady's aptitude for playing a part at short notice was remarkable. She fixed him with her conscious, perceptive eye and asked him if he spoke no French. Then, "Donnez!" she said briefly, and took the open guide-book. In the upper corner of the fly-leaf she traced a number, in a minute and extremely neat hand. Then she handed back the book and took up her palette again.

Our friend read the number: "2,000 francs." He said nothing for a time, but stood looking at the picture, while the copyist began actively to dabble with her paint. "For a copy, isn't that a good deal?" he asked at last. "Pas beaucoup?"

The young lady raised her eyes from her palette, scanned him from head to foot, and alighted with admirable sagacity upon exactly the right answer. "Yes, it's a good deal. But my copy has remarkable qualities, it is worth nothing less."

The gentleman in whom we are interested understood no French, but I have said he was intelligent, and here is a good chance to prove it. He apprehended, by a natural instinct, the meaning of the young woman's phrase, and it gratified him to think that she was so honest. Beauty, talent, virtue; she combined everything! "But you must finish it," he said. "finish, you know;" and he pointed to the unpainted hand of the figure.

"Oh, it shall be finished in perfection; in the perfection of perfections!" cried mademoiselle; and to confirm her promise, she deposited a rosy blotch in the middle of the Madonna's cheek.

Version 7

1. "I succumbed to the flattery of a man who wasn't there,"

2. "and in that moment of weakness I said yes."

3. "I'll be glad to read the work, I said"

4. "and do whatever I can to help."

5. "Sophie smiled at this"

6. "—whether from happiness or disappointment I could never tell—"

9. "unlatched the door"

10. "and let it swing open on its hinges."

11. "There you are, she said."

12. "There were boxes and binders and folders and notebooks cramming the

shelves"

13- "—more things than I would have thought possible."

14. "I remember laughing with embarrassment"

15. "and making some feeble joke"

16. "Then, all business,"

17. "we discussed the best way for me to carry the manuscripts out of the

apartment,"

18. "eventually deciding on two large suitcases."

19. "It took the better part of an hour"

20. "but in the end we managed to squeeze everything in"

21. "Clearly, I said, it was going to take me some time to sift through all the

material."

22. "Sophie told me not to worry, and then she apologized for burdening me with

such a job."

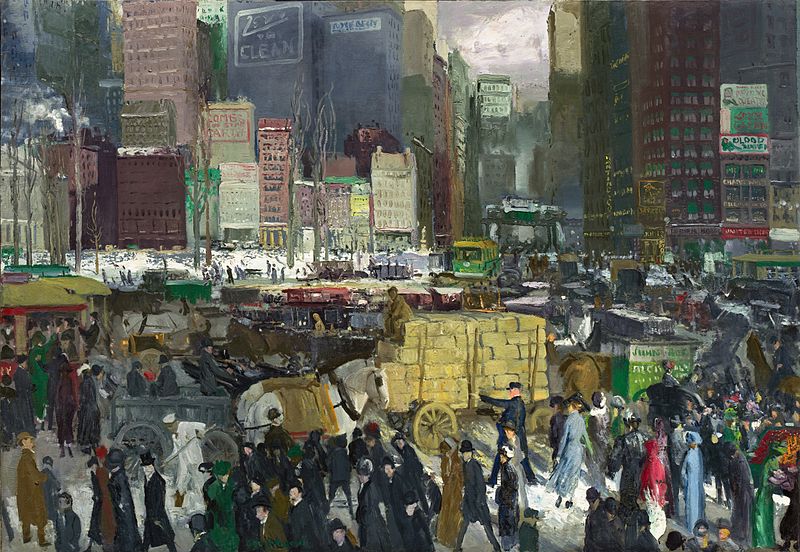

New York,1911, George Bellows

Stag at Sharkey's,1909, George Bellows

Upton Sinclair The Jungle, 1906

It was four o'clock when the ceremony was over and the carriages began to arrive. There had been a crowd following all the way, owing to the exuberance of Marija Berczynskas. The occasion rested heavily upon Marija's broad shoulders-it was her task to see that all things went in due form, and after the best home traditions; and, flying wildly hither and thither, bowling every one out of the way, and scolding and exhorting all day with her tremendous voice, Marija was too eager to see that others conformed to the proprieties to consider them herself. She had left the church last of all, and, desiring to arrive first at the hall, had issued orders to the coachman to drive faster. When that personage had developed a will of his own in the matter, Marija had flung up the window of the carriage, and, leaning out, proceeded to tell him her opinion of him, first in Lithuanian, which he did not understand, and then in Polish, which he did. Having the advantage of her in altitude, the driver had stood his ground and even ventured to attempt to speak; and the result had been a furious altercation, which, continuing all the way down Ashland Avenue, had added a new swarm of urchins to the cortege at each side street for half a mile.

This was unfortunate, for already there was a throng before the door. The music had started up, and half a block away you could hear the dull "broom, broom" of a cello, with the squeaking of two fiddles which vied with each other in intricate and altitudinous gymnastics. Seeing the throng, Marija abandoned precipitately the debate concerning the ancestors of her coachman, and, springing from the moving carriage, plunged in and proceeded to clear a way to the hall. Once within, she turned and began to push the other way, roaring, meantime, "Eik! Eik! Uzdaryk-duris!" in tones which made the orchestral uproar sound like fairy music.

"Z. Graiczunas, Pasilinksminimams darzas. Vynas. Sznapsas. Wines and Liquors. Union Headquarters"-that was the way the signs ran. The reader, who perhaps has never held much converse in the language of far-off Lithuania, will be glad of the explanation that the place was the rear room of a saloon in that part of Chicago known as "back of the yards." This information is definite and suited to the matter of fact; but how pitifully inadequate it would have seemed to one who understood that it was also the supreme hour of ecstasy in the life of one of God's gentlest creatures, the scene of the wedding feast and the joy-transfiguration of little Ona Lukoszaite!

She stood in the doorway, shepherded by Cousin Marija, breathless from pushing through the crowd, and in her happiness painful to look upon. There was a light of wonder in her eyes and her lids trembled, and her otherwise wan little face was flushed. She wore a muslin dress, conspicuously white, and a stiff little veil coming to her shoulders. There were five pink paper roses twisted in the veil, and eleven bright green rose leaves. There were new white cotton gloves upon her hands, and as she stood staring about her she twisted them together feverishly. It was almost too much for her-you could see the pain of too great emotion in her face, and all the tremor of her form. She was so young-not quite sixteen-and small for her age, a mere child; and she had just been married-and married to Jurgis,* (*Pronounced Yoorghis) of all men, to Jurgis Rudkus, he with the white flower in the buttonhole of his new black suit, he with the mighty shoulders and the giant hands.

Ona was blue-eyed and fair, while Jurgis had great black eyes with beetling brows, and thick black hair that curled in waves about his ears-in short, they were one of those incongruous and impossible married couples with which Mother Nature so often wills to confound all prophets, before and after. Jurgis could take up a two-hundred-and-fifty-pound quarter of beef and carry it into a car without a stagger, or even a thought; and now he stood in a far corner, frightened as a hunted animal, and obliged to moisten his lips with his tongue each time before he could answer the congratulations of his friends.

Version 8

Version coupée en unité de sens

1. "From where I sit, the story of Arthur Less is not so bad."

2. "Look at him: seated primly on the hotel lobby's plush round sofa,"

3. "blue suit and white shirt, legs knee-crossed"

4. "so that one polished loafer hangs free of its heel."

5. "The pose of a young man."

6. "His slim shadow is, in fact, still that of his younger self,"

7. "but at nearly fifty he is like those bronze statues in public parks that,"

8. "despite one lucky knee rubbed raw by schoolchildren,"

9. "discolor beautifully until they match the trees."

10. "So has Arthur Less, once pink and gold with youth, faded like the sofa he sits on,"

11. "tapping one finger on his knee and staring at the grandfather clock."

12. "The long patrician nose perennially burned by the sun"

13. "(even in cloudy New York October)."

14. "The washed-out blond hair too long on the top, too short on the sides – portrait of his

grandfather."

15. "Those same watery blue eyes."

16. "Listen: you might hear anxiety ticking, ticking, ticking away"

17. "as he stares at that clock, which unfortunately is not ticking itself."

18. "It stopped fifteen years ago. Arthur Less is not aware of this;"

19."he still believes, at his ripe age, that escorts for literary events arrive on time"

20. "and bellboys reliably wind the lobby clocks."

21."He wears no watch; his faith is fast."

9

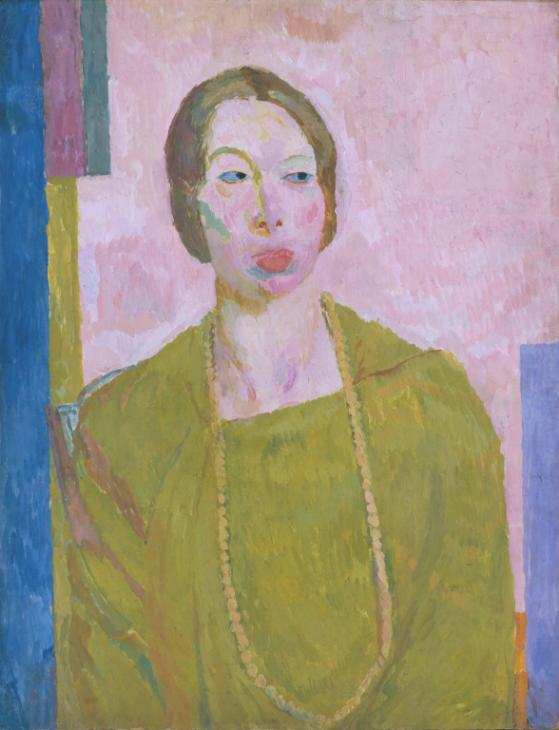

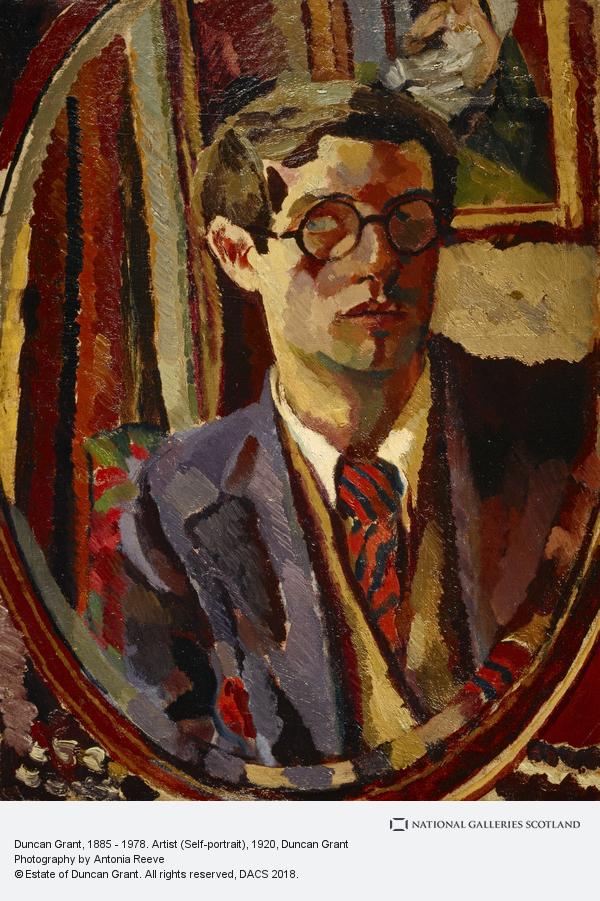

Post-impressionism

Virginia Woolf, Ms Dalloway, 1925

Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer's men were coming. And then, thought Clarissa Dalloway, what a morning--fresh as if issued to children on a beach.

What a lark! What a plunge! For so it had always seemed to her, when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which she could hear now, she had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air. How fresh, how calm, stiller than this of course, the air was in the early morning; like the flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet (for a girl of eighteen as she then was) solemn, feeling as she did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen; looking at the flowers, at the trees with the smoke winding off them and the rooks rising, falling; standing and looking until Peter Walsh said, "Musing among the vegetables?"--was that it?--"I prefer men to cauliflowers"--was that it? He must have said it at breakfast one morning when she had gone out on to the terrace--Peter Walsh. He would be back from India one of these days, June or July, she forgot which, for his letters were awfully dull; it was his sayings one remembered; his eyes, his pocket-knife, his smile, his grumpiness and, when millions of things had utterly vanished--how strange it was!--a few sayings like this about cabbages.

She stiffened a little on the kerb, waiting for Durtnall's van to pass. A charming woman, Scrope Purvis thought her (knowing her as one does know people who live next door to one in Westminster); a touch of the bird about her, of the jay, blue-green, light, vivacious, though she was over fifty, and grown very white since her illness. There she perched, never seeing him, waiting to cross, very upright.

For having lived in Westminster--how many years now? over twenty,--one feels even in the midst of the traffic, or waking at night, Clarissa was positive, a particular hush, or solemnity; an indescribable pause; a suspense (but that might be her heart, affected, they said, by influenza) before Big Ben strikes. There! Out it boomed. First a warning, musical; then the hour, irrevocable. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. Such fools we are, she thought, crossing Victoria Street. For Heaven only knows why one loves it so, how one sees it so, making it up, building it round one, tumbling it, creating it every moment afresh; but the veriest frumps, the most dejected of miseries sitting on doorsteps (drink their downfall) do the same; can't be dealt with, she felt positive, by Acts of Parliament for that very reason: they love life. In people's eyes, in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.

Version 9

Segment 1

A dense, layered, rose-tinted mist hovered above the lake

Segment 2

as Jordan Groves came over the Great Range and began his descent.

Segment 3

From

above, the mist obscured the pilot's view of the black surface of

the water.

There was no wind.

Segment

4

He cut his speed as close to a stall

as he dared

Segment 5

and

brought the biplane in gently, like laying a newborn baby into its

downy crib.

Traductions acceptées,

Segment 6

He felt the lake before he saw it,

Segment 7

and

when he knew the pontoons had settled squarely into the

glass-smooth

water he brought the engine

speed back up a notch

Segment 9

From

a distance of a hundred yards he could make out the shoreline

easily

enough, but little else,

Segment

10

nothing higher up on the shore, not

the clear blue sky above the mist or the

towering

pines and not the Coles's camp buildings

10

Post-impressionism

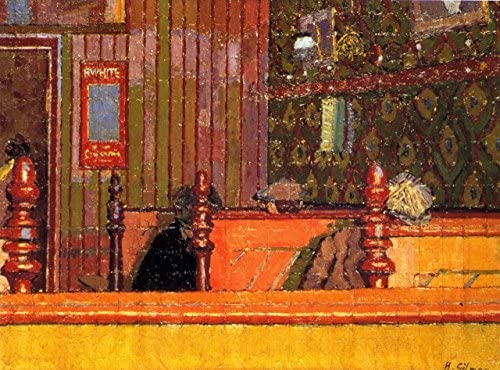

An Eating House, 1913, Harold Gilman

Clay, James Joyce Dubliners,1914

When she got outside the streets were shining with rain and she was glad of her old brown waterproof. The tram was full and she had to sit on the little stool at the end of the car, facing all the people, with her toes barely touching the floor. She arranged in her mind all she was going to do and thought how much better it was to be independent and to have your own money in your pocket. She hoped they would have a nice evening. She was sure they would but she could not help thinking what a pity it was Alphy and Joe were not speaking. They were always falling out now but when they were boys together they used to be the best of friends: but such was life. She got out of her tram at the Pillar and ferreted her way quickly among the crowds. She went into Downes's cake-shop but the shop was so full of people that it was a long time before she could get herself attended to. She bought a dozen of mixed penny cakes, and at last came out of the shop laden with a big bag. Then she thought what else would she buy: she wanted to buy something really nice. They would be sure to have plenty of apples and nuts. It was hard to know what to buy and all she could think of was cake. She decided to buy some plumcake but Downes's plumcake had not enough almond icing on top of it so she went over to a shop in Henry Street. Here she was a long time in suiting herself and the stylish young lady behind the counter, who was evidently a little annoyed by her, asked her was it wedding-cake she wanted to buy. That made Maria blush and smile at the young lady; but the young lady took it all very seriously and finally cut a thick slice of plumcake, parcelled it up and said: "Two-and-four, please." She thought she would have to stand in the Drumcondra tram because none of the young men seemed to notice her but an elderly gentleman made room for her. He was a stout gentleman and he wore a brown hard hat; he had a square red face and a greyish moustache. Maria thought he was a colonel-looking gentleman and she reflected how much more polite he was than the young men who simply stared straight before them. The gentleman began to chat with her about Hallow Eve and the rainy weather. He supposed the bag was full of good things for the little ones and said it was only right that the youngsters should

enjoy themselves while they were young. Maria agreed with him and favoured him with demure nods and hems. He was very nice with her, and when she was getting out at the Canal Bridge she thanked him and bowed, and he bowed to her and raised his hat and smiled agreeably, and while she was going up along the terrace, bending her tiny head under the rain, she thought how easy it was to know a gentleman even when he has a drop taken. Everybody said: "0, here's Maria!" when she came to Joe's house. Joe was there, having come home from business, and all the children had their Sunday dresses on. There were two big girls in from next door and games were going on. Maria gave the bag of cakes to the eldest boy, Alphy, to divide and Mrs. Donnelly said it was too good of her to bring such a big bag of cakes and made all the children say:

"Thanks, Maria."

But Maria said she had brought something special for papa and mamma, something they would be sure to like, and she began to look for her plumcake. She tried in Downes's bag and then in the pockets of her waterproof and then on the hallstand but nowhere could she find it. Then she asked all the children had any of them eaten it--by mistake, of course--but the children all said no and looked as if they did not like to eat cakes if they were to be accused of stealing. Everybody had a solution for the mystery and Mrs. Donnelly said it was plain that Maria had left it behind her in the tram. Maria, remembering how confused the gentleman with the greyish moustache had made her, coloured with shame and vexation and disappointment. At the thought of the failure of her little surprise and of the two and fourpence she had thrown away for nothing she nearly cried outright.

Version 10

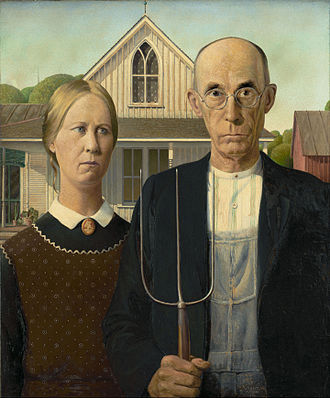

American Gothic, 1930, Grant Wood

People of Chilmark,1920, Thomas hart Benton

Faulkner, Sanctuary, 1931

From beyond the screen of bushes which surrounded the spring, Popeye watched the man drinking. A faint path led from the road to the spring. Popeye watched the man, a tall, thin man, hatless, in worn gray flannel trousers and carrying a tweed coat over his arm--emerge from the path and kneel to drink from the spring. The spring welled up at the root of a beech tree and flowed away upon a bottom of whorled and waved sand. It was surrounded by a thick growth of cane and brier, of cypress and gum in which broken sunlight lay sourceless. Somewhere, hidden and secret yet nearby, a bird sang three notes and ceased. In the spring the drinking man leaned his face to the broken and myriad reflection of his own drinking. When he rose up he saw among them the scattered reflection of Popeye's straw hat, though he had heard no sound. He saw, facing him across the spring, a man of under size, his hands in his coat pockets, a cigarette slanted from his chin. His suit was black, with a tight, high-waisted coat. His trousers were rolled once and caked with mud above mud-caked shoes. His face had a queer, bloodless color, as though seen by electric light; against the sunny silence, in his slanted straw hat and his slightly akimbo arms, he had that vicious depthless quality of stamped tin. Behind him the bird sang again, three bars in monotonous repetition: a sound meaningless and profound out of a suspirant and peaceful following silence which seemed to isolate the spot, and out of which a moment later tame the sound of an automobile passing along a road and dying away. The drinking man knelt beside the spring. "You've got a pistol in that pocket, I suppose," he said. Across the spring Popeye appeared to contemplate him with two knobs of soft black rubber. "I'm asking you," Popeye said. "What's that in your pocket?" The other man's coat was still across his arm. He lifted his other hand toward the coat, out of one pocket of which protruded a crushed felt hat, from the other a book. "Which pocket?" he said. "Dont show me," Popeye said. "Tell me." The other man stopped his hand. "It's a book." "What book?" Popeye said. "Just a book. The kind that people read. Some people do." "Do you read books?" Popeye said. The other man's hand was frozen above the coat. Across the spring they looked at one another. The cigarette wreathed its faint plume across Popeye's face, one side of his face squinted against the smoke like a mask carved into two simultaneous expressions. From his hip pocket Popeye took a soiled handkerchief and spread it upon his heels. Then he squatted, facing the man across the spring. That was about four o'clock on an afternoon in May. They squatted so, facing one another across the spring, for two hours. Now and then the bird sang back in the swamp, as though it were worked by a clock; twice more invisible automobiles passed along the highroad and died away. Again the bird sang.

Version 11

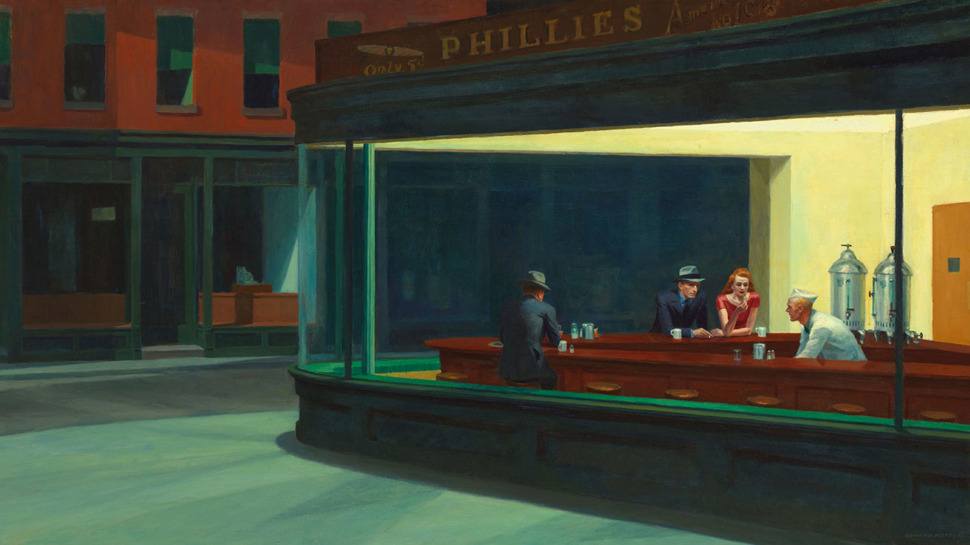

Nighthawks, 1942,Edward Hopper

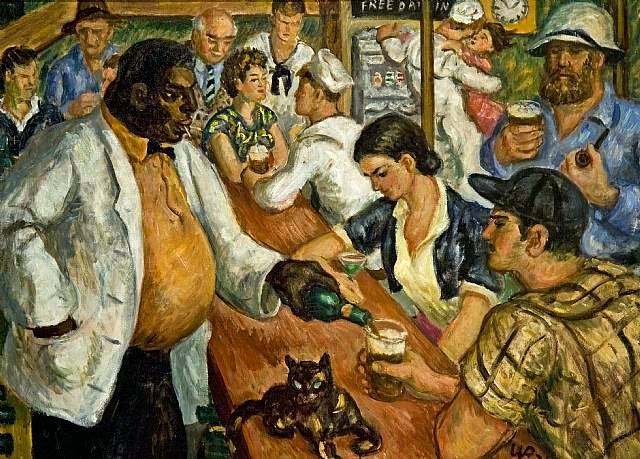

Sloppy Joe's,1936, Waldo Peirce

Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea, 1952

The boy carried the hot can of coffee up to the old man's shack and sat by him until he woke. Once it looked as though he were waking. But he had gone back into heavy sleep and the boy had gone across the road to borrow some wood to heat the coffee.

Finally the old man woke.

"Don't sit up," the boy said. "Drink this." He poured some of the coffee in a glass.

The old man took it and drank it.

"They beat me, Manolin," he said. "They truly beat me."

"He didn't beat you. Not the fish."

"No. Truly. It was afterwards."

"Pedrico is looking after the skiff and the gear. What do you want done with the head?"

"Let Pedrico chop it up to use in fish traps."

"And the spear?"

"You keep it if you want it."

"I want it," the boy said. "Now we must make our plans about the other things."

"Did they search for me?"

"Of course. With coast guard and with planes."

"The ocean is very big and a skiff is small and hard to see," the old man said. He noticed how pleasant it was to have someone to talk to instead of speaking only to himself and to the sea. "I missed you," he said. "What did you catch?"

"One the first day. One the second and two the third."

"Very good."

"Now we fish together again."

"No. I am not lucky. I am not lucky anymore."

"The hell with luck," the boy said. "I'll bring the luck with me."

"What will your family say?"

"I do not care. I caught two yesterday. But we will fish together now for I still have much to learn."

"We must get a good killing lance and always have it on board. You can make the blade from a spring leaf from an old Ford. We can grind it in Guanabacoa. It should be sharp and not tempered so it will break. My knife broke."

"I'll get another knife and have the spring ground. How many days of heavy brisa have we?"

"Maybe three. Maybe more."

"I will have everything in order," the boy said. "You get your hands well old man."

"I know how to care for them. In the night I spat something strange and felt something in my chest was broken."

"Get that well too," the boy said. "Lie down, old man, and I will bring you your clean shirt. And something to eat."

"Bring any of the papers of the time that I was gone," the old man said.

"You must get well fast for there is much that I can learn and you can teach me everything. How much did you suffer?"

"Plenty," the old man said.

"I'll bring the food and the papers," the boy said. "Rest well, old man. I will bring stuff from the drug-store for your hands."

"Don't forget to tell Pedrico the head is his."

"No. I will remember."

As the boy went out the door and down the worn coral rock road he was crying again.

That afternoon there was a party of tourists at the Terrace and looking down in the water among the empty beer cans and dead barracudas a woman saw a great long white spine with a huge tail at the end that lifted and swung with the tide while the east wind blew a heavy steady sea outside the entrance to the harbour.

"What's that?" she asked a waiter and pointed to the long backbone of the great fish that was now just garbage waiting to go out with the tide.

"Tiburon," the waiter said, "Eshark." He was meaning to explain what had happened.

"I didn't know sharks had such handsome, beautifully formed tails."

"I didn't either," her male companion said.

Up the road, in his shack, the old man was sleeping again. He was still sleeping on his face and the boy was sitting by him watching him. The old man was dreaming about the lions.

Version 12

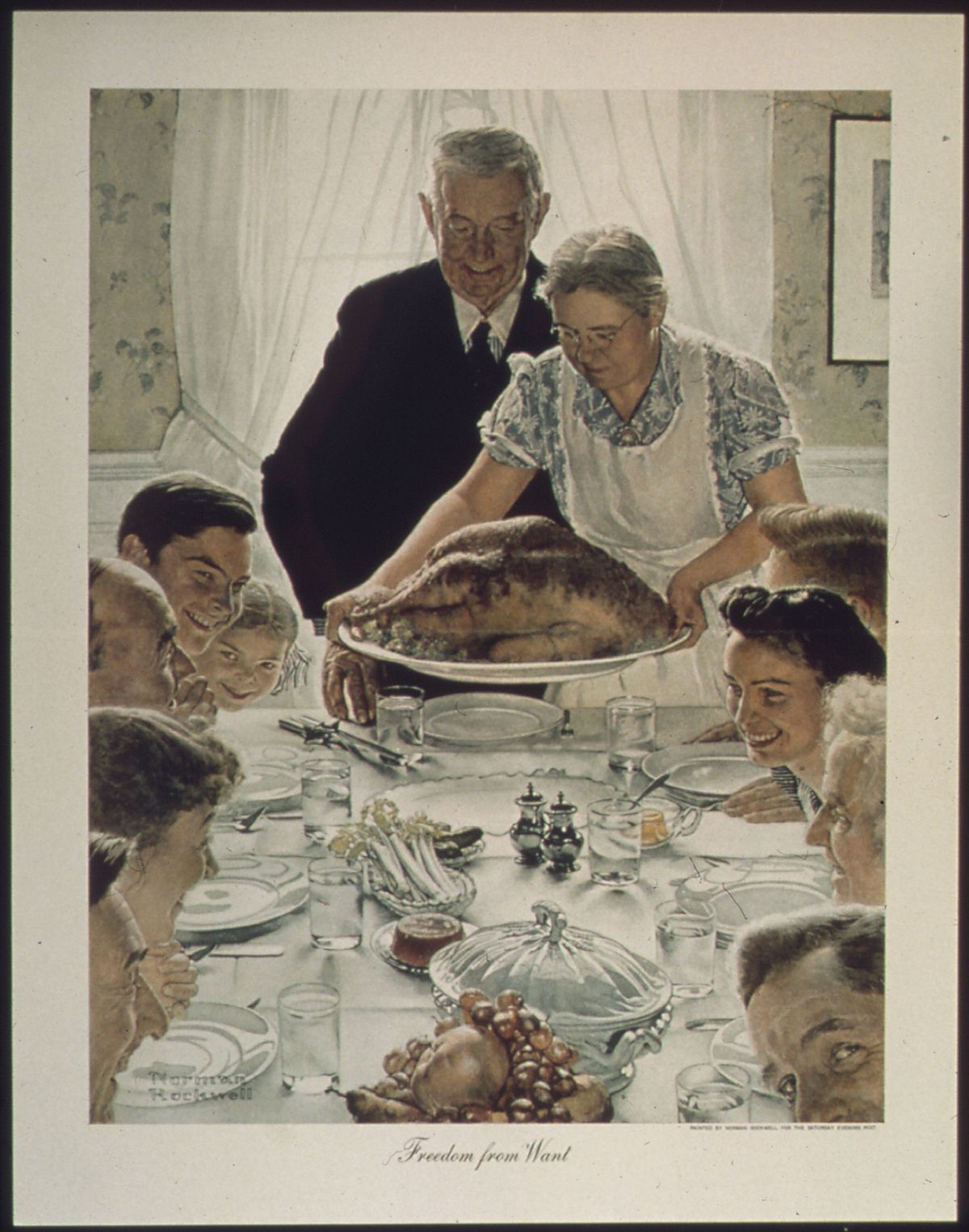

Freedom from Want,1943, Norman Rockwell

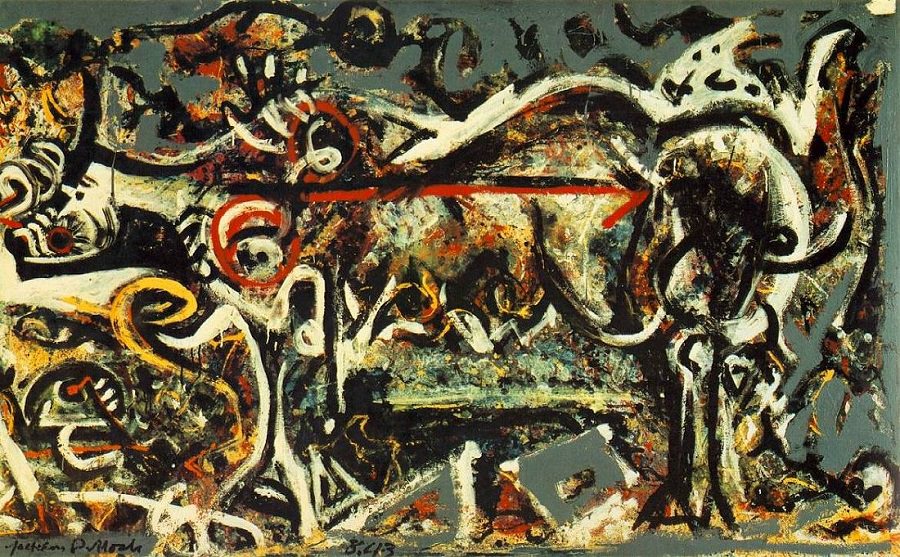

She-Wolf, 1943, Jackson Pollock

Jack Kerouac On the Road,1957

I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up. I had just

gotten over a serious illness that I won't bother to talk about, except

that it had something to do with the miserably weary split-up and my

feeling that everything was dead. With the coming of Dean Moriarty began

the part of my life you could call my life on the road. Before that I'd

often dreamed of going West to see the country, always vaguely planning

and never taking off. Dean is the perfect guy for the road because he

actually was born on the road, when his parents were passing through

Salt Lake City in 1926, in a jalopy, on their way to Los Angeles. First

reports of him came to me through Chad King, who'd shown me a few

letters from him written in a New Mexico reform school. I was

tremendously interested in the letters because they so naively and

sweetly asked Chad to teach him all about Nietzsche and all the

wonderful intellectual things that Chad knew. At one point Carlo and I

talked about the letters and wondered if we would ever meet the strange

Dean Moriarty. This is all far back, when Dean was not the way he is

today, when he was a young jailkid shrouded in mystery. Then news came

that Dean was out of reform school and was coming to New York for the

first time; also there was talk that he had just married a girl called

Marylou.

One day I was hanging around the campus and Chad and Tim Gray told me

Dean was staying in a cold-water pad in East Harlem, the Spanish Harlem.

Dean had arrived the night before, the first time in New York, with his

beautiful little sharp chick Marylou; they got off the Greyhound bus at

50th Street and cut around the corner looking for a place to eat and

went right in Hector's, and since then Hector's cafeteria has always

been a big symbol of New York for Dean. They spent money on beautiful

big glazed cakes and creampuffs.

All this time Dean was telling Marylou things like this: "Now,

darling, here we are in New York and although I haven't quite told you

everything that I was thinking about when we crossed Missouri and

especially at the point when we passed the Boon ville reformatory which

reminded me of my jail problem, it is absolutely necessary now to

postpone all those leftover things concerning our personal lovethings

and at once begin thinking of specific worklife plans . . ." and so on

in the way that he had in those early days.

I went to the

cold-water flat with the boys, and Dean came to the door in his shorts.

Marylou was jumping off the couch; Dean had dispatched the occupant of

the apartment to the kitchen, probably to make coffee, while he

proceeded with his love-problems, for to him sex was the one and only

holy and important thing in life, although he had to sweat and curse to

make a living and so on. You saw that in the way he stood bobbing his

head, always looking down, nodding, like a young boxer to instructions,

to make you think he was listening to every word, throwing in a thousand

"Yeses" and "That's rights." My first impression of Dean was of a young

Gene Autry-trim, thin-hipped, blue-eyed, with a real Oklahoma accent-a

sideburned hero of the snowy West. In fact he'd just been working on a

ranch, Ed Wall's in Colorado, before marrying Marylou and coming East.

Marylou was a pretty blonde with immense ringlets of hair like a sea of

golden tresses; she sat there on the edge of the couch with her hands

hanging in her lap and her smoky blue country eyes fixed in a wide stare

because she was in an evil gray New York pad that she'd heard about

back West, and waiting like a longbodied emaciated Modigliani surrealist

woman in a serious room. But, outside of being a sweet little girl, she

was awfully dumb and capable of doing horrible things. That night we

all drank beer and pulled wrists and talked till dawn, and in the

morning, while we sat around dumbly smoking butts from ashtrays in the

gray light of a gloomy day, Dean got up nervously, paced around,

thinking, and decided the thing to do was to have Marylou make breakfast

and sweep the floor. "In other words we've got to get on the ball,

darling, what I'm saying, otherwise it'll be fluctuating and lack of

true knowledge or crystallization of our plans." Then I went away.

Version 13

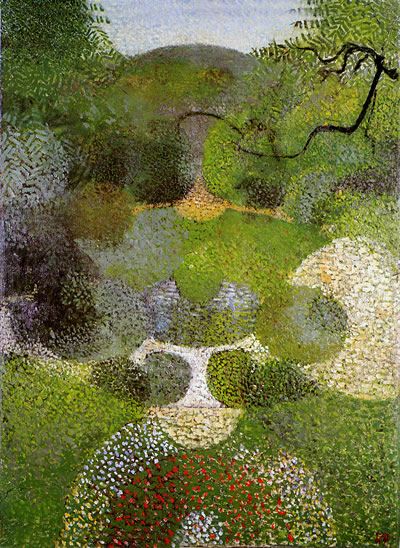

The Park, 1948, Victor Pasmore

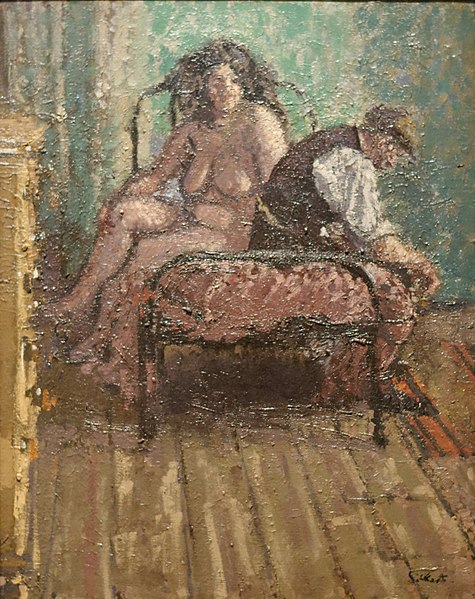

Mother Bathing Child, 1953, Jack Smith

"The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner", Alan Sillitoe, 1959

'THEY made a silly mistake, though,' the Professor of History said, and his smile, as Dixon watched, gradually sank beneath the surface of his features at the memory. 'After the interval we did a little piece by Dowland,' he went on; 'for recorder and keyboard, you know. I played the recorder, of course, and young Johns...' He paused, and his trunk grew rigid as he walked; it was as if some entirely different man, some impostor who couldn't copy his voice, had momentarily taken his place; then he went on again: '... young Johns played the piano. Versatile lad, that; the oboe's his instrument, really. Well anyway, the reporter chap must have got the story wrong, or not been listening, or something. Anyway, there it was in the Post Post as large as life: Dowland, yes, they'd got him right; Messrs Welch and Johns, yes; but what do you think they said then?' as large as life: Dowland, yes, they'd got him right; Messrs Welch and Johns, yes; but what do you think they said then?'

Dixon shook his head. 'I don't know, Professor,' he said in sober veracity. No other professor in Great Britain, he thought, set such store by being called Professor.

'Flute and piano.'

'Oh?'

'Flute and piano; not recorder and piano.' Welch laughed briefly. 'Now a recorder, you know, isn't like a flute, though it's the flute's immediate ancestor, of course. To begin with, it's played, that's the recorder, what they call a bec, that's to say you blow into a shaped mouthpiece like that of an oboe or a clarinet, you see. A present-day flute's played what's known as traverso, in other words you blow across a hole instead of...'

As Welch again seemed becalmed, even slowing further in his walk, Dixon relaxed at his side. He'd found his professor standing, surprisingly enough, in front of the Recent Additions shelf in the College Library, and they were now moving diagonally across a small lawn towards the front of the main building of the College. To look at, but not only to look at, they resembled some kind of variety act: Welch tall and weedy, with limp whitening hair, Dixon on the short side, fair and round-faced, with an unusual breadth of shoulder that had never been accompanied by any special physical strength or skill. Despite this over-evident contrast between them, Dixon realized that their progress, deliberate and to all appearances thoughtful, must seem rather donnish to pa.s.sing students. He and Welch might well be talking about history, and in the way history might be talked about in Oxford and Cambridge quadrangles. At moments like this Dixon came near to wishing that they really were. He held on to this thought until animation abruptly gathered again and burst in the older man, so that he began speaking almost in a shout, with a tremolo imparted by unshared laughter: 'There was the most marvellous mix-up in the piece they did just before the interval. The young fellow playing the viola had the misfortune to turn over two pages at once, and the resulting confusion... my word...'

Quickly deciding on his own word, Dixon said it to himself and then tried to flail his features into some sort of response to humour. Mentally, however, he was making a different face and promising himself he'd make it actually when next alone. He'd draw his lower lip in under his top teeth and by degrees retract his chin as far as possible, all this while dilating his eyes and nostrils. By these means he would, he was confident, cause a deep dangerous flush to suffuse his face.

Version 14

Anna died before dawn. To tell the truth, I was not there when it happened. I had walked out on to the steps of

the nursing home to breathe deep the black and lustrous air of morning. And in that moment, so calm and

drear, I recalled another moment, long ago, in the sea that summer at Ballyless. I had gone swimming alone, I

do not know why, or where Chloe and Myles might have been; perhaps they had gone with their parents

somewhere, it would have been one of the last trips they made together, perhaps the very last. The sky was

hazed over and not a breeze stirred the surface of the sea, at the margin of which the small waves were

breaking in a listless line, over and over, like a hem being turned endlessly by a sleepy seamstress. There were

few people on the beach, and those few were at a distance from me, and something in the dense, unmoving air

made the sound of their voices seem to come from a greater distance still. I was standing up to my waist in

water that was perfectly transparent, so that I could plainly see below me the ribbed sand of the seabed, and

tiny shells and bits of a crab's broken claw, and my own feet, pallid and alien, like specimens displayed under

glass.

John Banville, The Sea,2005.

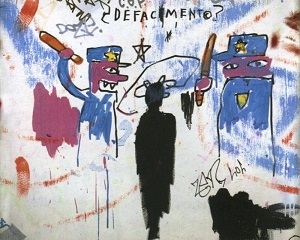

The Death of Michael Stewart,1993, Jean Michel Basquiat

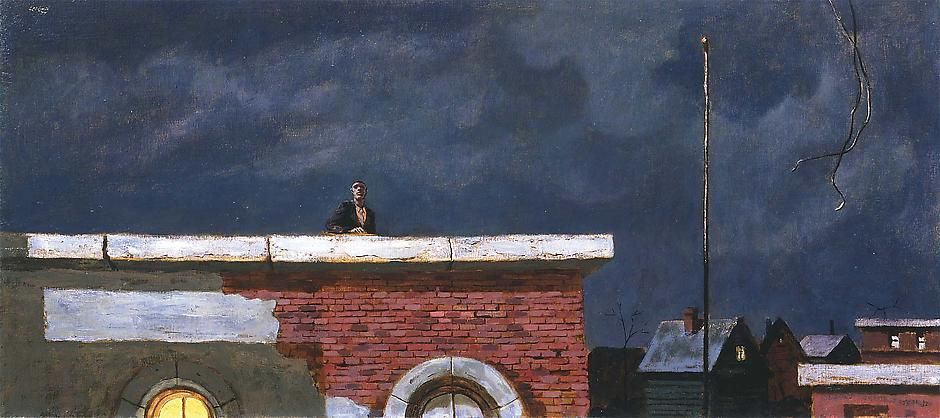

Untitled (Man on Rooftop),1954, Hughie Lee Smith

Version 15

An

easterly is the most disagreeable wind in Lyme Bay-Lyme Bay being that

largest bite from the underside of England's outstretched south-western

leg-and a person of curiosity could at once have deduced

several strong probabilities about the pair who began to walk down the

quay at Lyme Regis, the small but

ancient eponym of the inbite, one incisively sharp and blustery morning

in the late March of 1867.

The Cobb has invited what familiarity breeds for at least seven hundred

years, and the real Lymers will

never see much more to it than a long claw of old grey wall that flexes

itself against the sea. In fact, since it lies

well apart from the main town, a tiny Piraeus to a microscopic Athens,

they seem almost to turn their backs on

it. Certainly it has cost them enough in repairs through the centuries

to justify a certain resentment. But to a less

tax-paying, or more discriminating, eye it is quite simply the most

beautiful sea-rampart on the south coast of

England.

John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman, 1977.

Flea-Market Lady,1990-94, Duane Hanson

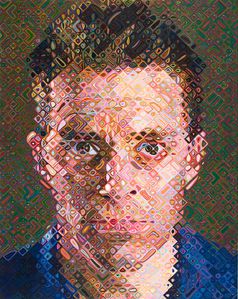

James,2004,Chuck Close

Raymond Carver, Cathedral,1981

Version 16

'Surely this'll do?' said Edward. 'It looks quite big enough and smart enough.'

Hoisted back to the London street, she saw them both reflected in the plate-glass of the shop window,

superimposed in transparency above silk and fur, gilt and leather, the swaggering dummies with blind

inscrutable gaze in their preposterous clothes. Their reflections, gliding above these sumptuous displays,

showed a shabby pair, distinctly down-at-heel, as sharply contrasted as the proletarian flotsam in some

Victorian street scene, dingy spectators of the nobs in their satin and feathers. The dummies in the windows

wore clothes so unlike Helen's that they might have stepped from some other culture: rainbow colours, fabrics

of wondrous texture and design, skirts like puffballs or split like a dancer's. The chairs upon which they sat or

leaned were gilded or of shining chrome and glass; bales of material were half unfurled to spill around more silk

and satin; jewellery was flung down in handfuls upon tables or simply on the ground. Prices, where stated at all,

were scribbled in decorative script upon tiny cards, an afterthought.

Penelope Lively, Passing on, 1989.

17

Post-modernism

The Vocabulary Guide : chapter 119

literary terms : similarity

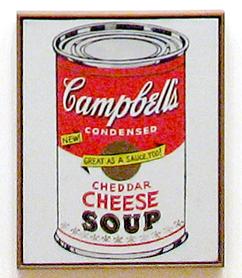

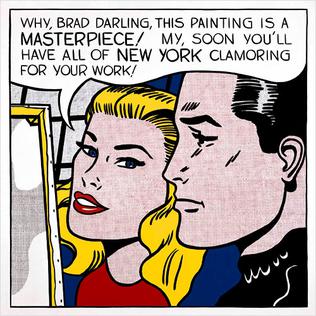

Masterpiece, 1962, Roy Lichtenstein

Paul Auster Auggie Wren's Christmas story, 1990